Increasing mental health problems among lower social classes in the United Kingdom

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Mental health problems seemed to have worsened during COVID-19, partly because of increasing income inequalities between higher and lower social classes. The problem of mental health inequalities is widespread all over Europe, but is especially visible in the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom is one of the countries with the highest prevalence of both mental health problems and income inequalities. The increasing mental health inequalities during COVID-19 are caused by different factors, such as increasing financial insecurity among lower social classes, government restrictions, unemployment and housing conditions. Implications for the future of the population of the United Kingdom appear to be alarming: mental health problems are likely to increase, next to income inequalities with consequences such as increasing health costs and decreasing quality of life. What can policies do to improve the current situation? Recommendations include increasing funding for mental health care, making mental health care more accessible in areas with many low class individuals and addressing income inequalities. Besides this, scientific research needs to investigate whether mental health inequalities are returning to the situation before COVID-19, are more permanent or even increasing and what can be done about this further.

INTRODUCTION

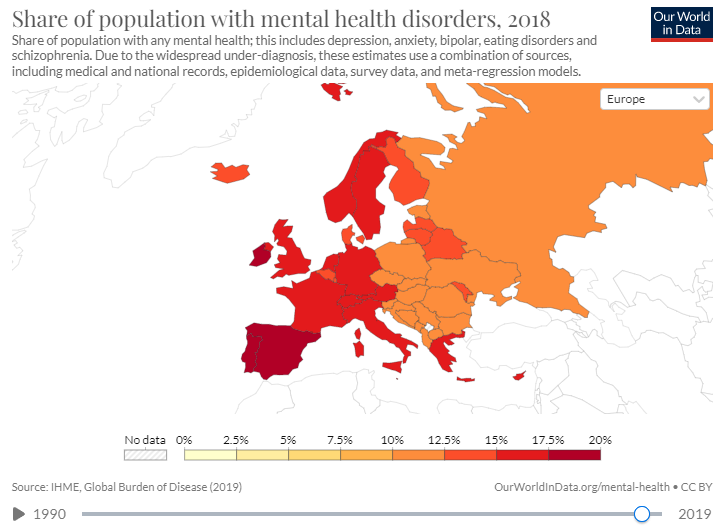

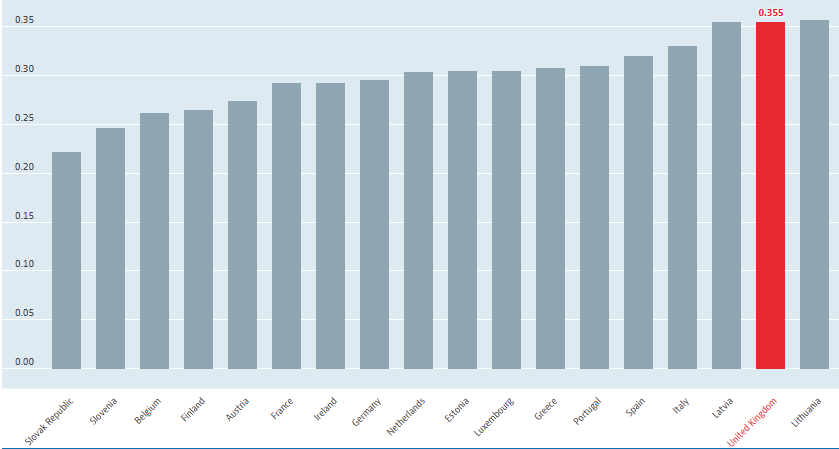

The United Kingdom is an interesting context to study in relation to social class differences and mental health, as it is one of the countries in Europe with both the highest amount of income inequality between low and high social classes AND one of the countries in Europe with the highest rates of mental health disorders [1] (Figure 1). Thus, already before COVID-19, the United Kingdom showed to be a country with one of the largest mental health inequalities between low and high social classes in Europe. During the COVID-19 pandemic, mental health inequality has increased in the United Kingdom due to a number of causes and factors. Mental health inequality between higher and lower social classes seems to be an increasing problem, and it is not clear yet whether the UK will return to the situation before COVID-19 or whether the inequality will continue to worsen.

Why is this problematic?

Mental health inequalities have severe, significant consequences for both individuals and society for several reasons, among which:

- People from lower social classes with more mental health problems, experience a lower quality of life. They are on average less happy, experience less life satisfaction and struggle to enjoy life [2].

- Mental health problems often require medication, treatment and/ or hospitalization. More mental health care problems leads to more health care costs, which is a problem for society as a whole [3].

- Mental health problems lead to reduced productivity within society, for example within the workplace. Serious mental disorders can lead to unemployment and lost wages, which will both lead to reduced economic growth in society [3].

More, severe mental health problems, like addiction, may lead to more individuals engaging in criminal activities to for example pay for drugs or drugs crime. Besides this, more individuals may be rendered homeless because of debts [3].

Mental health disorders can be defined as: “A wide range of mental health conditions, that affect your mood, thinking and behavior and significantly interfere with functioning in daily life, for example being able to work or care for yourself.” [4]. Examples of mental health disorders can be depression or anxiety disorders.

Social class can be defined as: ‘’A division of society in groups based on social and economic status’’ [5].

Social class is determined by the parental socio-economic status, but social and economic status can also be acquired through social mobility [5]. It is often defined through occupation and income. Social mobility is achieved when individuals move up or down the social ladder, for example, when switching jobs. For purposes of this brief, social class mostly divided in lower and higher social class. Individuals from a lower social class, are defined as individuals with a lower income, or an occupation that results in a lower income, often unskilled or skilled labourers [5]. People with a higher social class are individuals with higher incomes and occupations in the service sectors, often managers or knowledge workers. Social class has social consequences. Research shows that individuals from lower social classes om average have had less education, experience more stress, experience less life satisfaction and often have more health problems than people from higher social classes [6]. People from lower social classes have a, on average, 10 years lower life expectancy than people from higher social classes [6], which makes the social consequences of social class very real.

The mental health care system of the United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, there is universal health care. Mental health care is free for all citizens and is given by the National Health Service [7]. Individuals that want to access mental health care must go to their general practitioner and get a referral for a mental health professional. The NHS claims a maximum waiting time of 18 weeks between the first contact with the mental health service and the first appointment [7]. The mental health system is currently under strain. This is due to increasing demand for service and to funding cuts made by the government [7]. Waiting times are long, which increases the severity of complaints and access to specialist services are limited in some more rural and impoverished areas. A solution for the long waiting list is private insurance, which is expensive. This insurance is often only taken out by the upper class and leads to faster and more accessible mental health services. This leads to increasing inequalities between higher and lower social classes, individuals from lower social classes cannot afford private insurance and must wait longer for health care, while they often live in areas with less healthcare available [7].

The aim of this brief is to provide an overview of the state-of-the-art scientific research concerning the relation between social class differences and mental health problems during COVID-19. The focus is on England, a country where there were already large mental health inequalities between social classes before COVID-19.

STATE-OF-THE-ART: MENTAL HEALTH AND SOCIAL CLASS

Mental health in the United Kingdom

Research shows that approximately 1 in 4 people in the United Kingdom experience a mental health problem, such as symptoms of anxiety or depression, each year [4]. The prevalence of mental health disorders shows that 10% of the population of the United Kingdom has been diagnosed with a mental health disorder between July 2019 and March 2020 [8]. Thus, mental health problems seem to be a large problem in the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom is one of countries in Europe with the highest prevalence of mental health symptoms and mental health disorders [1]. Research shows that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevalence in the United Kingdom of mental health disorder rose to 19% in June 2020 and 21% by January to March 2021. In September and October 2022 this prevalence fell to 16% [8]. It is not clear whether the prevalence has fallen during the current situation.

Social class differences in the United Kingdom

According to empirical studies, executed in the United Kingdom, income inequality remains stable, yet relatively high compared to other developed countries in Europe [9].

The link between social class and mental health

A strong link has been found between social class and mental health [6]: People from lower social classes experience more mental health problems than people from higher social classes.

Mechanisms:

- People from lower social classes have less income and experience more financial insecurity [5].

- This leads to more stress about providing for yourself and the family on a micro level, which leads to more mental health symptoms, such as depression and anxiety, and a lower life satisfaction [5].

- Besides this, people from lower social classes often have less accessibility to mental health services, which also leads to more untreated mental health problems among individuals from lower social classes [6].

Increasing mental health inequality during COVID-1

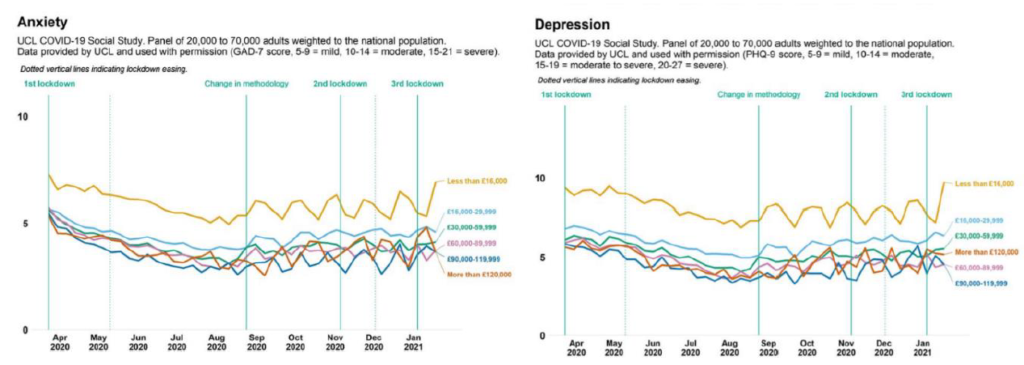

The literature shows that lower class individuals report a stronger decline in health and economic wellbeing due to the covid pandemic. This can be seen in Figure 3, in which the higher income individuals experience less depression and anxiety during the pandemic, compared to lower class individuals. High income individuals also experience a higher life satisfaction than lower class individuals [11].

Causes and factors of mental health inequalities during COVID-19

- Financial insecurity

Research shows that individuals from lower social classes are more affected by the increased financial insecurity due to COVID-19 [10]. Before COVID-19, individuals from lower social classes already experienced more financial insecurity than the higher social classes, which lead to stress and mental problems. During COVID-19, due to more unemployment, less income and less resources, the gap in financial security between the social classes has increased [12].

- Unemployment has risen, because jobs in certain sectors, where lower class individuals often work, have disappeared, e.g., restaurants, bars and public transport [12].

- Besides this, there seems to be less opportunity for people from lower social classes to work from home. This is often not possible in non-essential unskilled/ skilled labour work [12].

- In addition, people from lower social classes often have less income and are more affected by the reduction in income, caused by the pandemic and the consequent economic crisis [12].

- There are less resources, for example, savings or buffers to compensate for those losses. Those factors lead to increasing financial insecurity in lower social classes and lead to more stress among those classes, which in term leads to more mental health problems, such as anxiety or depression [12].

- Besides this, there is less income available for individuals from lower social classes to afford mental health services, whereas individuals from higher social classes can afford private mental health care without having to wait on long waitlists [12].

- Unexpected increases in living expenses

Lower social classes are more impacted by unexpected increases in living expenses than the higher classes. They have less savings and buffers to compensate for increases in living expenses: a bigger proportion of the income goes to living expenses. This leads to increased stress and mental health problems in individuals from lower social classes [12].

- Technology

Individuals from lower social classes often had less income and money available to buy the technology needed during the pandemic, in comparison to individuals from higher social classes. Examples of this are laptops, internet connection devices, computer programs or office equipment. This led to increased stress among people from lower social classes about income and job opportunities, e.g. stress because of opportunities that jobs offer to work from home, which leads to more mental health problems [13].

- Government restrictions

Besides this, the lower social classes have more trouble with the government restrictions, e.g. not being able to use public transport (for example when individuals cannot afford a car), buying mouth masks, tests or soap affected the lower classes more, because they had less money to spend, which led to more stress and more mental health problems [14].

Link to institutional context of the United Kingdom The issue of government restrictions links to legal and political institutions in the United Kingdom. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was the party gate scandal, involving the prime minister of the United Kingdom, Boris Johnson and his staff. The party fate scandal referred to the rule-breaking social gatherings that took place at the residence of Boris Johnson, despite lockdown restrictions that prohibited indoor gatherings. The scandal caused public outrage and started questions about the reliability and transparency of the government of the United Kingdom. Besides this, the scandal highlighted issues of social inequality, including mental health inequalities. It highlighted on the one hand the perceived lack of empathy of the government towards the people that lost others or suffered financially due to the restrictions and on the other hand the failure of the government to address these inequalities. It can be argued that the scandal has worsened mental health further, because it eroded trust in public institutions and worsened feelings of anxiety and distress among vulnerable populations, such as people from lower social class and lower incomes [15].

- Housing conditions

Lower class individuals were more often stuck in a smaller house, while working from home or quarantining. Research shows that participants living in houses of more than 120 square meters showed lower psychological impact, lower stress, anxiety and depression symptoms than those living in less than 30 square. Moreover, people with access to an outdoor space (e.g., garden, balcony) had higher wellbeing scores and better mental health [16]. Reasons for these are that, when living in a small house, there is less space for physical activities, relaxing and setting up home offices. Not having a garden limits opportunities for exercise and getting fresh air and sunlight, which leads to increased stress and mental health symptoms [16]. Because of this, differences in housing conditions can lead to increased stress and mental health problems in the lower social classes.

- Availability of mental health services

Lower class individuals often live in areas where there is less availability of mental health services [17]. This leads to less opportunity for individuals from lower social classes to access mental health care services. Due to COVID-19, there was less availability of mental health services. More mental health workers became sick or trapped at home, while there was a larger need for care, which lead to less access and opportunity for lower class individuals in particular. Besides this, lower social class individuals often have had less education on health and health communication (how to communicate health concerns and access health services), while higher social class individuals found it easier to access and find mental health services when needed [17].

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE FUTURE

The critical conditions of the United Kingdom with regard to mental health and social class during COVID-19, depict a negative perspective for individuals from lower social classes that experience mental health inequality.

The aspects analysed in the policy brief are explained here in terms of future implications.

Mental health – Mental health was already a problematic topic in the United Kingdom before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, due to the pandemic, mental health problems have worsened. This led to an increase in depression and anxiety symptoms in the British population, especially among individuals from lower social classes. There seems to be some recovery, in the statistics, however, the prevalence of mental health disorders has not returned to the situation before COVID-19. This worsening of mental health will have serious, detrimental consequences on individuals and society, such as decreasing life satisfaction and decreasing quality of life, especially for the lower social classes. Quality of life might continue to deteriorate, especially if the mental health inequality continues, for the lower social classes. This might lead to more inequality and more division in society. There already is more mental health inequality than before the COVID-19 pandemic. Besides this, the worsening of mental health problems will lead to increasing health care costs and could lead to more crime, addiction and homelessness in the United Kingdom. It is very important to watch this trend in the future to investigate if mental health care will recover to the previous situation.

Income inequality – The United Kingdom already has a large gap in incomes between lower and higher social classes, one of the highest gaps throughout Europe. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, these income inequalities have increased. Lower social classes struggle more with financial insecurity, increased living expenses, affording technology and housing condition during COVID-19. Working from home seems to be an increasing trend, which makes the factors affording technology and housing condition still relevant factors, even after de pandemic. It seems to be the case that this greater gap in income inequality will not naturally disappear or go back to the situation before COVID-19, because those factors will not recover spontaneously. Compared to other European countries, with less income inequalities, the United Kingdom will remain one of the countries with the most mental health problems and income inequalities, which could lead to more division and controversy within the country. This division and controversy can already be seen in the Brexit, where approximately half of the population envisioned a future within the European Union and half of the population did not. It can also be seen in the political climate in the controversy around Boris Johnson and the downfall of Theresa May as the shortest serving prime minister. In sum, increasing income and mental health inequalities seem to be creating more controversy and division in the United Kingdom, especially in combination with other political and societal factors.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Even though literature shows the mechanisms and causes of why lower-class individuals struggle more with mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as financial insecurity, unemployment, housing conditions and affordable technology, the literature does not provide information about the current situation after COVID-19 yet. It is unclear if the problem has returned to the situation before COVID-19, or if class-based inequalities in mental health might have worsened or progressed.

Because of this, it seems to be very important that this topic remains monitored and researched. It is recommended that more research should be directed at investigating whether individuals from lower social classes, with lower incomes, still experience more mental health problems at this current moment. It is recommended to do this research with large scale surveys, easily accessible to lower class individuals, who might not have technology available. Because of this, researchers should pay attention to the population they use in their research and add enough people from lower social classes. This could be done by, for example, visiting cities/neighbourhoods where lower class individuals live and promoting research in those areas. Furthermore, it is very important to research how the mental health inequalities can be battled and what effective policies would look like. Even if the problem might have returned to the situation before COVID-19, mental health inequalities between social classes seems to still remain a substantial problem in society.

What are the recommendations for policy makers in the United Kingdom? Recommendations can also be directed at improving the mental health of lower class individuals or addressing the causes of those mental health inequalities. First of all, the government should invest more in improving the mental health of the lower social classes, through different actions:

- The government of the United Kingdom should increase funding for mental health services. Increasing the funding for mental health services could improve the mental health of all people, regardless of social class, which is beneficial for everybody. But beside this, the government should increase the availability of mental health services, particularly in areas where help is limited. By making mental health services more accessible in areas where many people from lower social classes live, they are more likely to have the opportunity to access these services and improve their mental health. This can help to ensure that individuals have access to mental health services, regardless of their socio-economic status.

- Besides this, increasing social benefits could help individuals from lower social classes to pay for private mental health services and improve their mental health.

- The government could increase access to mental health services in schools, in particular schools in areas with a high proportion of children from parents with lower social class/lower income. Mental health problems often start during adolescence/early adulthood. Prevention or early treatment, among vulnerable groups, often children from lower social class parents, might be essential in reducing mental health inequalities among social classes in society. This might also help children from lower social classes learn to develop better health communication skills.

- It is recommended that the government addresses the income inequalities, for example by providing more extensive social benefits to lower income groups or unemployed groups. In this way, individuals from lower social classes experience less stress and worries, and less mental health problems.

- In addition to this, the government could provide individuals from lower social classes with certain fees to afford the technology needed during the pandemic, for example affordable laptops.

- There should be more attention to policies that support affordable housing, education and employment opportunities for lower social classes.

Sources

1. Dattani, S., Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2021). Mental Health. Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health

2. Rajmil, L., Herdman, M., Ravens-Sieberer, U., Erhart, M., Alonso, J., & European KIDSCREEN Group. (2014). Socioeconomic inequalities in mental health and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in children and adolescents from 11 European countries. International Journal of Public Health, 59, 95-105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-013-0479-9

3. Ngui, E. M., Khasakhala, L., Ndetei, D., & Roberts, L. W. (2010). Mental disorders, health inequalities and ethics: A global perspective. International Review of Psychiatry, 22(3), 235-244 https://doi.org/10.3109/

09540261.2010.485273

4. World Health Organization. (2022). Mental Disorders. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/news room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders

5. Henry, P. (2001). An examination of the pathways through which social class impacts health outcomes. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 1(3), 165-177.

6. Muntaner, C., Borrell, C., & Chung, H. (2007). Class relations, economic inequality and mental health: Why social class matters to the sociology of mental health. Mental Health, Social Mirror, 5, 127-141. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-36320-2_6

7. NHS. (2023). Mental Health. Retrieved from: https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/ 8. Office For National Statistics. (2021). Coronavirus and depression in adults, Great Britain: July to August 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.

ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/coronavirusanddepressioninadultsgreatbritain/julytoaugust2021

9. Office for National Statistics. (2023). Statistical bulletin, Household income inequality, UK: financial year ending 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/personalandhouseholdfinances/income

andwealth/bulletins/householdincomeinequalityfinancial/financialyearending2022#cite-this statistical-bulletin

10. OECD. (2023). Income inequality (indicator). Retrieved from: https://data.oecd.org/inequality/income-inequality.htm

11. Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. (2022). COVID-19 mental health and wellbeing surveillance: report. Retrieved from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19- mental-health-and-wellbeing-surveillance-report

12. Claes, N., Smeding, A., & Carré, A. (2021). Mental Health Inequalities During COVID-19 Outbreak: The Role of Financial Insecurity and Attentional Control. Psychol, 61, 327-340. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb.1064.

13. Gibson, B., Schneider, J., Talamonti, D., & Forshaw, M. (2021). The impact of inequality on mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 62(1), 101-104. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000272

14. Zhang, Y., Ding, Y., Xie, X., Guo, Y., & van Lange, P. A. (2023). Lower class people suffered more (but perceived fewer risk disadvantages) during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 26(1), 39-51. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12543

15. BBC. (2021). Downing Street Christmas party: What were the Covid rules at the time? Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-59577129

16. Bonati, M., Campi, R., & Segre, G. (2022). Psychological impact of the quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic on the general European adult population: A systematic review of the evidence. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 31, 224-228. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796022000051

17. Viswanath, K., & Ackerson, L. K. (2011). Race, ethnicity, language, social class, and health communication inequalities: a nationally-representative cross-sectional study. PloS One, 6(1), 145- 150. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0014550

18. Hannigan, B., & Allen, D. (2006). Complexity and change in the United Kingdom’s system of mental health care. Social Theory & Health, 4, 244-263.