Sade Zollner (2097843) & Fieke Esveld (2092668) | Social Policy and Social Risks

Introduction

In 2015, the social policy of student financing in the Netherlands underwent a transformation with the implementation of the social loan system. The social policy of student financing shifted from a basic grant to a loan-oriented structure. By shifting this policy, the government aimed to address perceived inequalities of the past system and contribute to the fiscal responsibility of individuals in higher education. As of early 2023, the total student debt, accrued under this system, has surged to 28.2 billion euros [1]. Because of the high debt of the student population, financial risks for their future occurred. That is why the government decided to quit this system and shift back to a basic grant system in September 2023.

The shift from a grant-oriented system to a loan-oriented system has come with negative consequences for the affected students [2]. To be more precise, research has shown that the study loan system has led to divergent outcomes for students with varying financial backgrounds, suggesting Matthew effects [2] [3]. In this research note, we will delve into these negative outcomes and explain how the study loan system affected students with divergent income levels differently. Specifically, the research question that we seek to answer is: ‘Did the Dutch study loan system lead to Matthew effects, making the existing differences between students from different income classes greater ?’.

Understanding the differential outcomes of the study loan system based on income is valuable, since it is of importance for policymakers [4]. With the knowledge gained from this research note, policymakers can work towards developing a system that minimizes the negative consequences that are disproportionately affecting lower-income students. It will assist policymakers in creating a fair distribution of education costs among students, regardless of their socioeconomic backgrounds, during student grant reforms. Understanding the nuances with this paper can help shape a new system that fosters equal opportunities and reduces the social and economic disparities associated with student financing.

From a scientific perspective, the Dutch study loan system provides a valuable case study for researchers examining education, economics, and social policy. The findings contribute to a growing amount of literature on the complexities of student financing systems and its relationships with societal dynamics [5] [6]. The outcomes of the Dutch study loan system offers insights that are also relevant outside of the Netherlands, shaping discussions on the design and impact of social policies for higher education worldwide.

Study loan system explained

The origin of the social loan system can be traced back to the ideology of the PvdA (Labour Party) in the Netherlands. The party stated that the traditional basic grant system increases socio-economic inequality. Under the previous system, students from affluent backgrounds received the same financial support as those from economically disadvantaged families. The PvdA wanted to rectify this by introducing a new system so that the financial burden of education did not disproportionately fall on certain segments of society, stating that “the baker didn’t have to pay for the education of the lawyer’s son” [7].

This perspective found resonance with other political entities, including GroenLinks (Green party) and D66 (Democratic party). The VVD (People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy) also supported the concept, viewing it as a means to shift student financing towards being more of an ‘individual responsibility.’ Moreover, the introduction of the loan system aligned with the broader governmental objective of significant budget cuts. Proponents of the social loan system anticipated a saving of one billion euros, with the intention that this freed-up budget would be reinvested in higher education, ensuring that students could still benefit from improved educational quality [7].

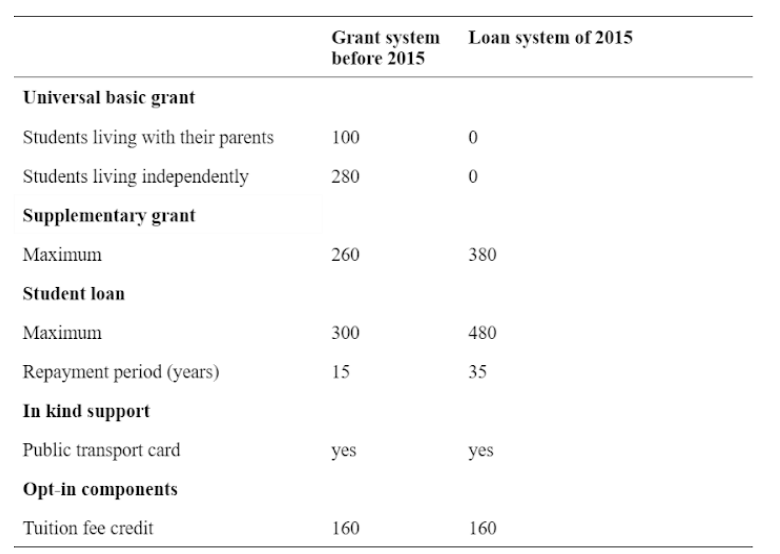

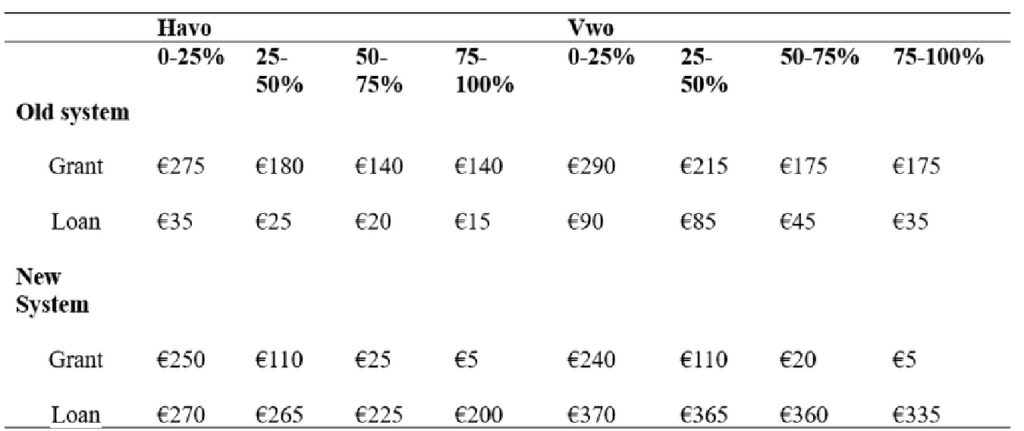

In the academic year 2015/’16 the social loan system was introduced in higher education. The loan arrangements were expanded in comparison to the system before, while an additional grant for students from low-income groups was retained (see table 1). The overarching rationale for the new policy was the belief that investing in higher education significantly enhances job market prospects, justifying a greater financial commitment from students and their families during their educational journey. The government, in its 2012 agreement, emphasized the intention to allocate the saved budget towards enhancing the overall quality of education [8] [1] .

Social policy and Matthew effects

The occurrence of Matthew effects, as first described by Robert Merton [10], is worth considering when implementing or reviewing social policies. This principle describes a context in which those that are already in an advantaged position in society are more capable of extending that advantage compared to those that are in a disadvantaged position. In welfare states, Matthew effects can occur because social policy outcomes are often more in favor of the middle class than of the poor [11]. This is somewhat contradictory to the original goal of most welfare states, which is to alleviate poverty by assisting the people that are most in need, since they are also most likely to face social risks [12] [13]. Nonetheless, Matthew effects can occur as a result of social policy measures because the middle class is often more capable of influencing the policy process itself, and to get more out of welfare state systems than the lower class [11].

Although this has hardly been studied yet, Matthew effects could also occur as a result of study loan systems. Price [14], for example, argues that study loan systems can lead to more stratification between social classes. Since students from low-income families have less financial resources to afford going to college, they are often dependent on loans to be able to attend college. This increases the educational debt burden of students from low-income families compared to students from more affluent families, which can be considered a clear example of the Matthew effect.

Empirical analysis

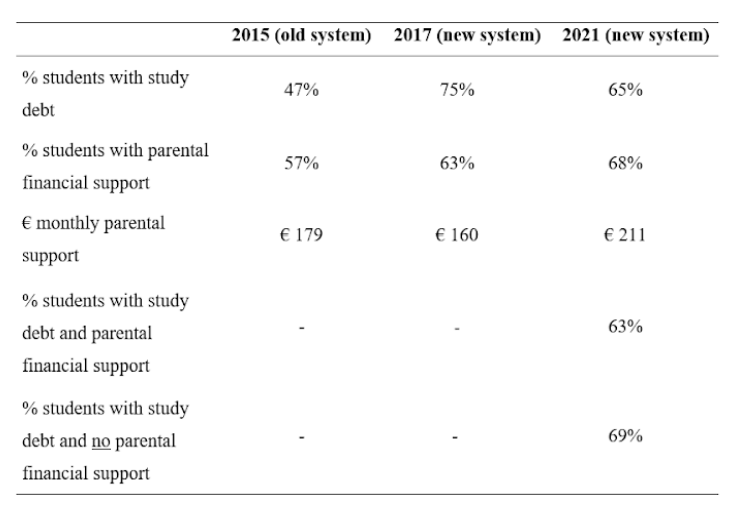

In the past years, independent Dutch research institute Nibud has looked into the financial situation of both students that were part of the old study funding system and students that were part of the new study funding system. First of all, Nibud has looked into the percentage of students that received financial support from their parents, and the amount of money that they received in general on a monthly basis across several years. The findings (table 2) of these studies show that in the new system, more students received parental financial support than students in the old system [3] [15]. This indicates that students became more dependent on their parents’ financial support over the years, and eventually became financially independent later on than in previous years [15].

Furthermore, the study loan system was based on the idea that parents contributed to their childrens’ study costs and that only students from low-income families received an additional study grant from the government. However, parents that fall just above the modal household income are not always able to contribute to their childrens’ study costs, which increases the risk of inequality of opportunity between students [15].

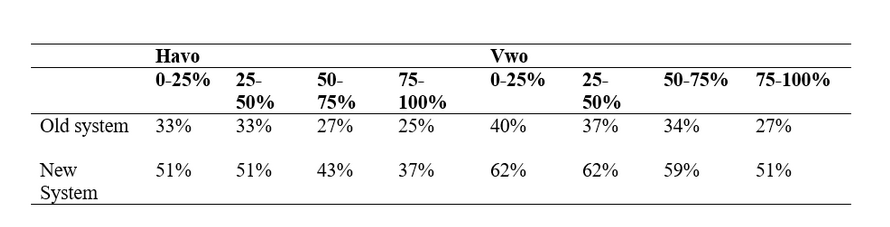

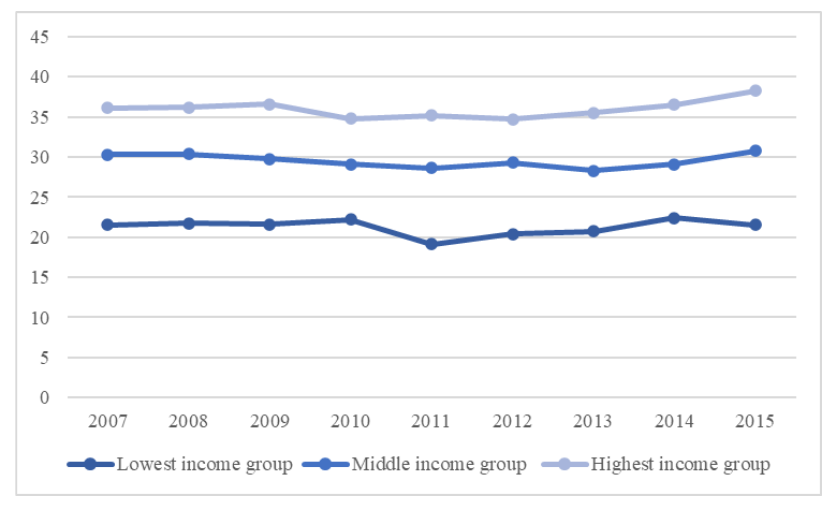

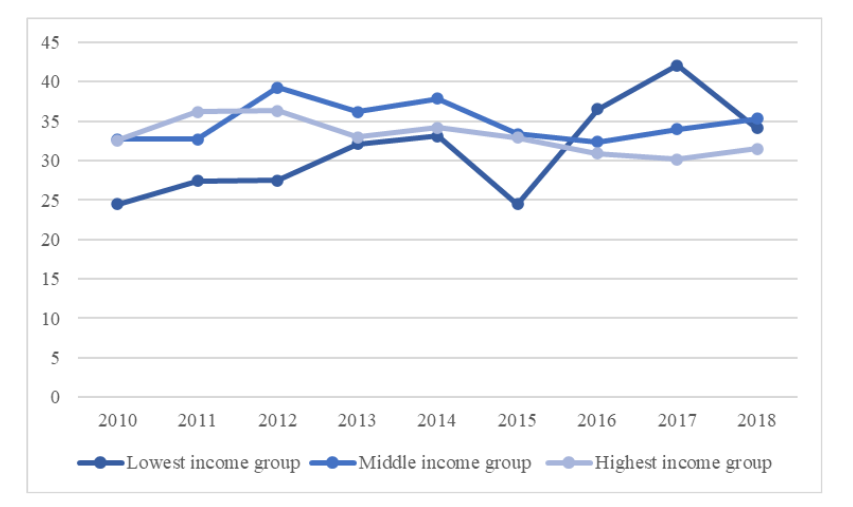

The findings of Groen and Houtsma [15], on behalf of Nibud, correlate with the findings of Bolhaar, Kuijpers, & Zumbuehl [16], suggesting inequality of opportunity between students based on income differences. They reveal a noteworthy trend in the impact of the study loan system on students from different income backgrounds. In their findings, they state that across all income groups, the percentage of students opting for loans has increased since the study loan system was implemented (see table 3). However, their data shows a more pronounced rise among students from lower-income quartiles who completed their secondary education at the havo-level compared to their higher-income counterparts.

*Note: the values are extracted from a graph. Therefore, there might be a level of potential imprecision inherent in graphical data interpretation.

Before the study loan system, there were already differences in loan take up between income groups. For students that completed the vwo-level education, the difference in loan uptake has not changed since the study loan system was implemented and remains approximately 10% between low and high income groups. In contrast, students that completed the havo-level education experience an increase between the low and high income groups in loan take-up. This difference grew from around 7% to 14%.

While all income groups borrow more than they have lost due to the elimination of the basic grant, this overcompensation is more pronounced among lower-income students. Students from the vwo-level exhibit an increase in loan amounts across all income groups (see table 4). However, this increase is the biggest for the lowest income group, resulting in a substantial overcompensation of approximately 230 euros, compared to around 130 euros for higher-income groups. Among students that finished the havo-level, these disparities are even more pronounced, as lower-income students experience a larger increase in borrowed amounts. Consequently, havo-level students in the lowest income group are the ones taking on the most additional debt, borrowing approximately 235 euros more per month despite receiving about 25 euros less in grants.

*Note: the values are extracted from a graph. Therefore, there might be a level of potential imprecision inherent in graphical data interpretation.

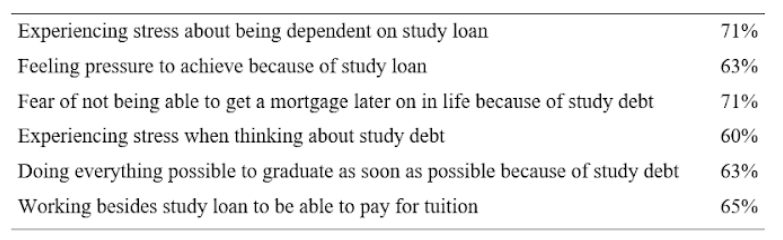

Above findings indicate that students that did not receive parental financial support applied for study loans more often, and that students from low-income households took on higher study loans in general. These students are not only left with higher debts, but also with financial concerns as a result of their study loans. As is shown in table 5, students with a study debt often experience financial stress, pressure to achieve and a higher workload due to their dependence on study loans [17]. Previous research indicates that financial stress negatively affects study results, which can extend the time to graduation, driving the costs of education for students that do not receive parental financial support even further [18] [19].

Results of study loan system on students’ wellbeing [17]

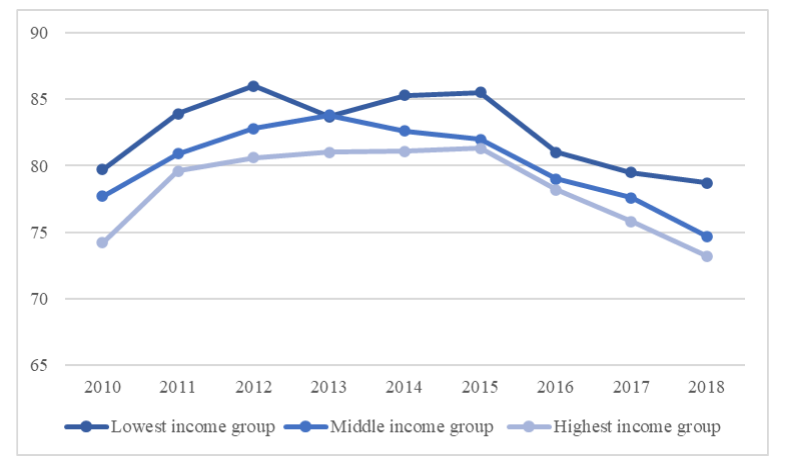

The CBS [2] also analyzed the effect of the study loan system on students of different income households. The likelihood of changing fields of study, obtaining a bachelor’s degree within the nominal duration, and enrolling in a master’s program were key areas of their research. Results revealed that, since the introduction of the loan system, the percentage of students changing their field of study within four years has decreased, suggesting a potential positive impact on academic stability. The percentage of students obtaining a bachelor’s degree within four years increased for cohorts starting in 2014 and 2015 compared to the 2012 cohort (see figure 6). However, the socioeconomic differences persisted, with students from less affluent backgrounds having a lower likelihood of timely bachelor’s degree completion due to them having more financial concerns [2].

The transition to master’s programs saw significant changes post-2015. The percentage of students transitioning directly from the bachelor to the master dropped, especially for cohorts starting from 2016 onwards (see figure 7). This decline was more pronounced among students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, indicating potential challenges faced by these students in pursuing postgraduate education within the nominal duration.

While the percentage of students completing a one-year master’s program within one year showed fluctuations, students from less affluent backgrounds had consistently lower rates (see figure 8). The trend, however, saw a notable increase for the 2016 cohort from lower-income groups. This suggests a changing dynamic in postgraduate education attainment influenced by socioeconomic factors under the loan system, suggesting that especially students from the least affluent groups feel pressure to complete the master’s program within the nominal duration due to study costs [2].

Conclusions

The goal of this research note was to find out whether the Dutch study loan system, marked by the shift from a basic grant to a loan-oriented structure, has led to Matthew effects among students from different income classes. The implementation of the study loan system has had significant implications for students across different income backgrounds. The findings of this study reveal a widening gap in study debts among students, with those from lower-income families facing increased financial burdens and experiencing heightened levels of financial stress. The observed inequalities align with the notion of Matthew effects, where those already advantaged in society tend to further extend their advantages, exacerbating existing inequalities.

The social and economic consequences are visible since students that did not receive parental financial support were forced to apply for student loans, causing financial pressures and academic stress, which in turn often leads to even greater debts. Furthermore, students that needed to take on a study loan during the period the social loan system was in place are in a less certain financial position after they graduate than students who received parental financial support. Although the study loan system has positively influenced academic stability, the persistence of socio-economic differences in timely bachelor’s degree completion show the challenges faced by less affluent students. The decline in transitioning to master’s programs, especially among lower socio-economic backgrounds, shows that this group faces more obstacles in pursuing postgraduate education within the nominal duration. From a policy perspective, these findings emphasize the need for a more nuanced and equitable approach to student financing, ensuring that financial policies do not disproportionately burden students from less affluent backgrounds.

Discussion

This research note involves some limitations, since we have used several secondary data sources for our empirical analysis. While the use of multiple data sources expands the amount of information, it also means that the study is constrained by the methodologies, definitions, and interpretations used by the original data providers. Our study is therefore dependent on the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the data presented in these reports, and any biases or shortcomings in the original analyses may carry over to this study [20]. Additionally, the lack of direct control over the data collection and analysis processes in the original reports restricts the ability to explore specific nuances that might be crucial for a more in-depth understanding of the implications of the study loan system. Future research might benefit from using primary data collection to address these limitations and provide a more nuanced perspective of the study loan system’s impact on students from varying income backgrounds.

Since the first students that were part of the study loan system graduated in 2019, data on the long-term effects of this system is restricted at the time of this research. Therefore, future research might want to conduct a comprehensive examination of the long-term effects of the study loan system, considering the effect of study debt on the possibility of buying a house and the financial well-being of graduates. Additionally, exploring the potential interplay of other socio-economic factors, such as race and ethnicity, with the study loan system would provide a broader understanding of its impact on diverse student populations. Also, future research might need to look into alternative financing models that prioritize equal opportunities, diminish social and economic disparities, and contribute to the overarching goal of accessible and affordable higher education for all.

Reference list

[1] Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (2023). Studieschuld opgelopen tot 28 miljard euro. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. Retrieved from Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek website: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2023/41/studieschuld-opgelopen-tot-28-miljard-euro

[2] Van den Berg, L. & Van Gaalen, R. (2021). Hoe vergaat het studenten in het leenstelsel? Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. Retrieved from Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek website: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/longread/statistische-trends/2021/hoe-vergaat-het-studenten-in-het-leenstelsel-

[3] Van der Schors, A., Schonewille, G., & Van der Werf, M. (2015). Studentenonderzoek 2015. Achtergrondstudie bij Handreiking Student & Financiën. Retrieved from Nibud website: https://www.nibud.nl/onderzoeksrapporten/nibud-studentenonderzoek-2015/

[4] Britton, J., Van der Erve, L., & Higgins, T. (2019). Income contingent student loan design: Lessons from around the world. Economics of Education Review, 71, 65-82. Doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.06.001

[5] Castleman, B. L., & Long, B. T. (2016). Looking beyond enrollment: The causal effect of need-based grants on college access, persistence, and graduation. Journal of Labor Economics, 34(4), 1023-1073. Retrieved from: https://www-journals-uchicago-edu.tilburguniversity.idm.oclc.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1086%2F686643

[6] Joensen, J. S. & Mattana, E. (2021). Student Aid Design, Academic Achievement, and Labor Market Behavior: Grants or Loans? Retrieved from SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3028295 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3028295

[7] Wet Studievoorschot hoger onderwijs (34.035). (z.d.). Eerste Kamer der Staten-Generaal. Retrieved from: https://www.eerstekamer.nl/wetsvoorstel/34035_wet_studievoorschot_hoger?df1=vgi8gqaw8fs6

[8] Regeerakkoord (2012). Bruggen slaan. Regeerakkoord VVD-PvdA.

[9] Bolhaar, J., Kuijpers, S., Webbink, D., & Zumbuehl, M. (2023). Does replacing grants by income-contingent loans harm enrolment? Retrieved from Centraal Planbureau website: https://www.cpb.nl/vermindert-het-vervangen-van-studiebeurzen-door-een-sociaal-leenstelsel-de-onderwijsinschrijvingen

[10] Merton, R.K. (1973). The sociology of science. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

[11] Gal, J. (1998). Formulating the Matthew Principle: on the role of the middle classes in the welfare state. Scandinavian Journal of Social Welfare, 7(1), 42-55. Doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2397.1998.tb00274.x

[12] Pintelon, O., Cantillon, B., Van den Bosch, K., & Whelan, C. T. (2013). The social stratification of social risks: The relevance of class for social investment strategies. Journal of European social policy, 23(1), 52-67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928712463156

[13] Dewilde, C. (2020). Poverty and access to welfare benefits. In Greve, B. (Ed.), Routledge international handbook of poverty (pp. 268-284). London, England: Routledge.

[14] Price, D. V. (2004). Educational debt burden among student borrowers: An analysis of the baccalaureate & beyond panel, 1997 follow-up. Research in Higher Education, 45(7), 701-737. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:RIHE.0000044228.54798.4c

[15] Groen, A. & Houtsma, N. (2021). Nibud studentenonderzoek 2021. Onderzoek naar de geldzaken van hbo- en wo-studenten. Retrieved from Nibud website: https://www.nibud.nl/onderzoeksrapporten/nibud-studentenonderzoek-2021/

[16] Bolhaar, J., Kuijpers, S., & Zumbuehl, M. (2020). Effect Wet studievoorschot op toegankelijkheid en leengedrag. Retrieved from Centraal Planbureau website: https://www.cpb.nl/sites/default/files/omnidownload/CPB-Policy-Brief-Effect-Wet-studievoorschot-op-toegankelijkheid-en-leengedrag.pdf

[17] Letkiewicz, J., Lim, H., Heckman, S., Bartholomae, S., Fox, J., & Montalto, C. P. (2014). The path to graduation: Factors predicting on-time graduation rates. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 16(3), 351-371. http://dx.doi.org/10.2190/CS.16.3.c

[18] Van Vreden, W. & Thijssen, R. (2019). Impact van leenstelsel op welbevinden studenten. Kwantitatief onderzoek naar de relatie tussen het leenstelsel en het welbevinden van studenten in Nederland. Retrieved from ISO website: https://www.iso.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Onderzoek-Impact-leenstelsel-op-welbevinden-studenten-Motivaction-definitief.pdf

[19] Baker, A.R., & Montalto, C.P. (2019). Student loan debt and financial stress: Implications for academic performance. Journal of College Student Development, 60(1), 115-120. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2019.0008

[20] Black, P. (2018). Secondary data analysis: the good, the bad and the problematic. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526441409