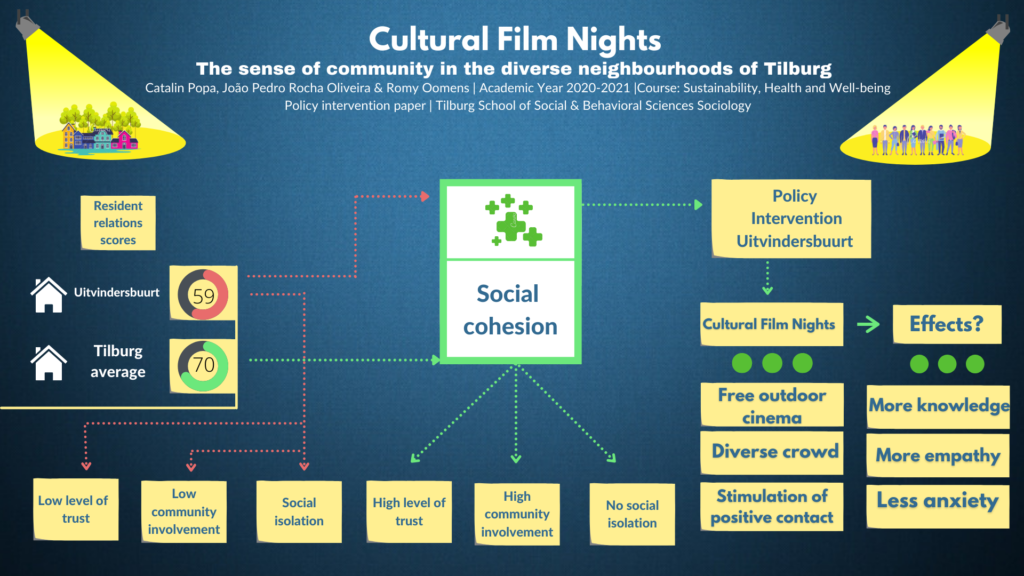

As the phrase “birds of a feather flock together’’ suggests, we seek contact with people who are similar to us [1]. While this tendency seems unharmful from the outset, it can become detrimental in heterogeneous neighbourhoods like the Uitvindersbuurt, where people of different ethnicities live together. Why? This preference for homophily has been shown to create strong divides between different ethnic groups [2]. Therefore, creating a sense of community in the Uitvindersbuurt is a difficult task that requires a solid intervention to diminish these divides. We propose an intervention called “Film Nights’’ that manages to use the diversity of the residents in the Uitvindersbuurt to their own advantage by bringing together the neighbourhood in a social setting.

This intervention unites people of different ethnicities at an open-air cinema, where movies and documentaries depicting a variety of cultures will be shown. This enables them to learn more about each other’s ethnic backgrounds. Moreover, it provides the residents with the opportunity to connect with those they otherwise would probably have never met. We think this intervention is worthwhile, considering its firm theoretical basis. The idea rests on Allport’s intergroup contact theory, which suggests that lengthy, positive contact between ethnic groups leads to more positive attitudes [3]. These positive attitudes are attained through an increase in empathy and knowledge, as well as a decrease in anxiety [4].

By organizing monthly events where people can voluntarily gather to watch a cultural movie and converse, we assume attendees will become more tolerant and connected towards one another. These positive attitudes can even spread to uninvolved ethnic groups, making this contact strategy even more powerful in increasing positive intergroup attitudes in Uitvindersbuurt as a whole [5].

From ethnic segregation to a united community

Research shows that Uitvindersbuurt scores very low on ‘resident relations’ with a disappointing 5.9 out of 10, compared to the average of 7 out of 10 in Tilburg as a whole [6]. This was confirmed by our own fieldwork in the neighbourhood, which showed that the streets were empty, with little to no conversation.

We thus intended to increase the sense of community with our intervention, as signs of connectedness and attachment in Uitvindersbuurt were considerably lacking. We believe the positive attitudes attained through the established positive contact at the events reduce the prejudice that leads to social exclusion.

In this way, the social networks that exist between different ethnic groups will be broadened as well as strengthened.

This will result in a more tightly knitted community, in which everyone feels seen, heard and appreciated. These broadened social networks also provide access to new information and opportunities, which could help people succeed socioeconomically [7]. This is especially beneficial for our target group, the ethnic minorities in Uitvindersbuurt, as they are more often unemployed and could use new labor-market opportunities [8]. All in all, our intervention should thus be able to lift the score on ‘resident relations’ for the Uitvindersbuurt, as it solidifies this once fractured community. Moreover, it should improve the health and well-being of the already disadvantaged ethnic minorities by increasing their chances on the labor-market.

Obstacles to overcome

The realization of the Film Nights intervention is not without obstacles, however. In order for the idea to work, people need to be willing to participate. We need volunteers to organize the event, but are aware that people may not want to commit the effort, because of a lack of interest or even time. By emphasizing that volunteering can contribute to personal growth through the development of individual skills, we hope to overcome this problem.

Furthermore, attendance might be an issue, as it is crucial that we attract a diverse, and large group of residents for our event. However, we believe that many people will be interested in attending for the mere fact that we offer a free and fun leisure option in their neighbourhood. The widespread divulgation of the event will also attract residents from all ethnicities and ages, as we purposely use different means: social networks, local newspapers and posters across the neighbourhood. Lastly, the intervention might suffer from a slow start or a gradual decline in attendance. By evaluating experiences of the attendees, we hope to improve each new version of the event, so that we can be responsive to their desires and needs. This will increase the chances of attendees returning, but it also attracts newcomers.

If these difficulties are all accounted for, our plan could make people realize that we are more or less the same, despite our different ethnicities. This could transform the Uitvindersbuurt in a place where people do not have an ‘us-vs-them mentality’, but rather a ‘we’ mindset: one that diminishes the divisions between ethnic groups, so that the residents can all face forward and flourish as one.

References

[1] Byrne, D. (1961). Interpersonal attraction and attitude similarity. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 62(3), 713.

[2] McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual review of sociology, 27(1), 415-444.

[3] Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

[4] Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2008). How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta‐analytic tests of three mediators. European journal of social psychology, 38(6), 922-934.

[5] Vezzali, L., & Giovannini, D. (2012). Secondary transfer effect of intergroup contact: The role of intergroup attitudes, intergroup anxiety and perspective taking. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 22(2), 125-144.

[6] RIGO. (2019). Leefbaarheidsmonitor Tilburg. Retrieved from https://www.lemontilburg.nl/lemon2019/

[7] Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American journal of sociology, 78(6), 1360-1380.

[8] Gracia, P., Vázquez-Quesada, L., & Van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2016). Ethnic penalties? The role of human capital and social origins in labour market outcomes of second-generation Moroccans and Turks in the Netherlands. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42(1), 69-87.