Intimate partner violence in the most gender equal countries of the world

Introduction

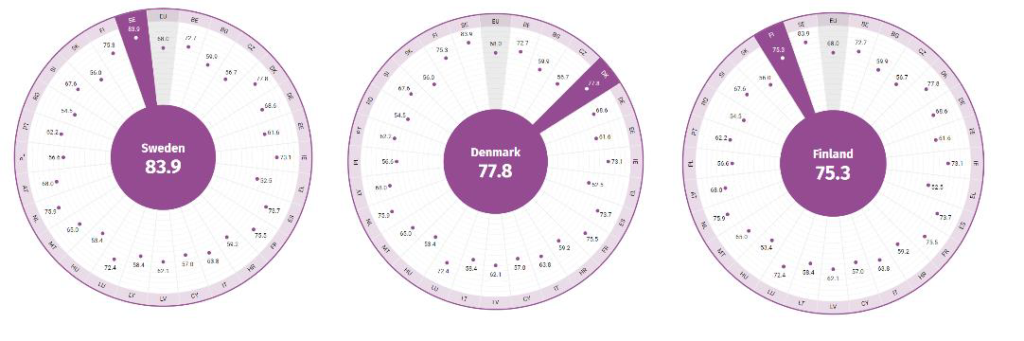

The concept of gender equality is an important topic and hotly debated all over the world, in particular when talking about gender inequality. Whereas gender equality refers to a situation in which people of all genders have equal rights and opportunities [1], gender inequality entails ´´…the discrimination on the basis of sex or gender causing one sex or gender to be routinely privileged or prioritized over another.´´ [2] When trying to assess a country’s gender equality level, you could look at the Gender Equality Index (GEI). The GEI is an important tool that has been used to measure gender equality in countries of the European Union. In this index, member states are given a score from 1 to 100 indicating their full equality (100) or their full inequality (1). The core domains for measurement of the GEI are work, money, knowledge, time, power, health, and violence. [3] Overall, when examining this index, you’ll find that the Nordic countries (for this policy brief focusing on Denmark, Finland, and Sweden) score high on gender equality, as Sweden (83.9), Denmark (77.8), and Finland (75.3) rank among the top 5 on the GEI, which you can see in Figure 1. These results are not surprising as Nordic countries are also often viewed as being very gender equal countries.

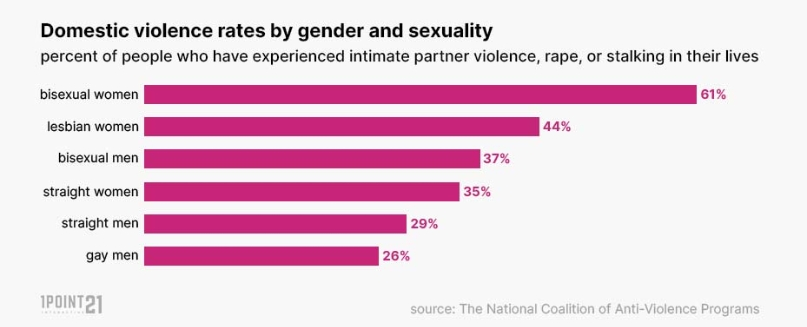

Achieving gender equality is important for many reasons, and one of them is the prevention of violence against women. Despite the fact that the relationship between gender inequality and violence is a very complex one, research in fact shows that gender inequality is a significant predictor for violence of men against women (which is also therefore on of the core domains of the GEI) [4], and in particular when talking about intimate partner violence (IPV). Intimate partner violence, as the term itself already partly explains, refers to the violence that happens within a romantic relationship, or after that relationship has ended. IPV can take on many forms, such as physical or mental abuse, stalking, or sexual violence [5]. IPV is an urgent issue worldwide and one of its most common forms is the violence against women, also known as intimate partner violence against women (IPVAW). For example, looking at the U.S., you can see that in figure 2 it is depicted how often men and women suffer from domestic violence, where women significantly suffer more often compared to men. [6] When talking about IPV, a term that is also often used is domestic abuse or domestic violence, which refers to the same thing and is important to know when reading about this topic.

Despite the fact that Nordic countries are considered and also measured as being the most gender equal countries in Europe, something shocking is happening in these countries. Research on IPV shows that Denmark, Finland, and Sweden, all part of the top 5 of the European Gender Equality Index, show high percentages of women experiencing physical, sexual or psychological intimate partner violence, namely 32%, 30%, and 28%, respectively. [7] This is significantly higher than the EU in general, which has an average of 22% of women suffering from IPV. This surprising relationship between increased gender inequality and increased intimate partner violence is called the Nordic Paradox, and goes against this reasoning on intimate partner violence and gender equality: “High prevalence IPV against women and high levels of gender equality would appear contradictory, but these apparently opposite statements appear to be true in Nordic countries, producing what could be called the ‘Nordic paradox’.’’ [8] In the next section, we will be looking at the possible mechanisms behind this paradox with the use of an overview of state-of-the-art scientific research.

The violent partners’ rotation hypothesis

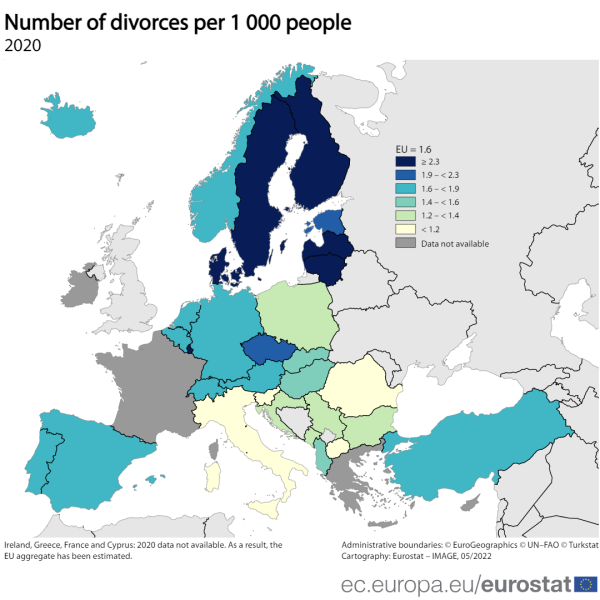

Even though it has been hard for researchers to scientifically explain the Nordic paradox, there have been some studies that have looked at possible mechanisms behind this ongoing issue. A possible mechanism that could be used to explain the Nordic paradox is the violent partners’ rotation hypothesis (VPR hypothesis). The VPR hypothesis poses that in countries where women more easily leave violent partners, intimate partner violence is higher compared to countries in which women have more difficulties with ending their violent relationship and are rather trapped in such relationships. [9] In Nordic countries, union dissolution (simply said, ‘breaking up’) is more common and this hypothesis could thus serve as an explanation for the Nordic paradox. For example, looking at figure 4, you see that Denmark, Finland, and Sweden (the main focus of this policy brief) are in the top countries regarding number of divorces in 2022 per 1000 people. According to the VPR hypothesis, intimate partner violence is thus higher in such countries.

The backlash effect

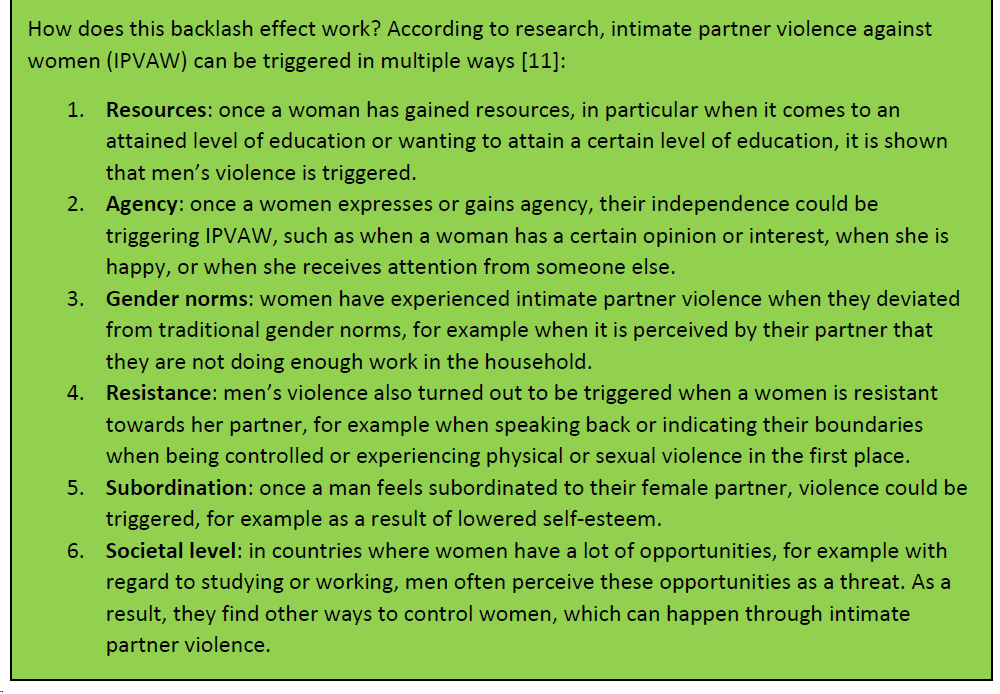

However, perhaps a more comprehensive explanation that is used more often to understand this paradox is the backlash effect, and is also closely related to the violent partners’ rotation hypothesis. The backlash effect refers to the idea that men could become more violent in countries with high gender equality levels due to perceived loss of power as a result of women’s increased empowerment in such countries. [10] As already mentioned, in countries in which union dissolution is more common due to high levels of independency (and empowerment), intimate partner violence is more common perhaps as a result of this perceived loss of power. Many researchers have dived further into the idea of the backlash effect and have found multiple domains in which this perceived loss of power could occur, and which are described in figure 4 below.

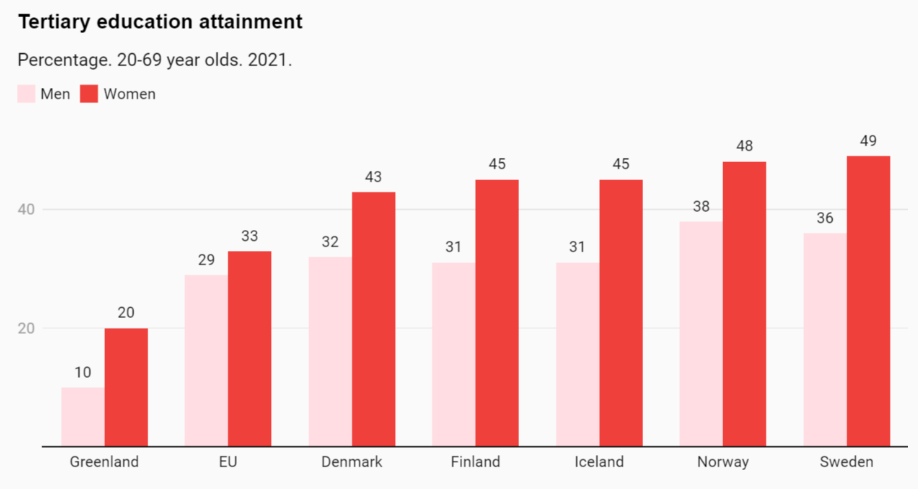

The domains that are used to explain intimate partner violence against women that are described in the textbox above could be used to partly explain the Nordic paradox. As already mentioned in the introduction, Nordic countries are often perceived and also measured to be very gender equal. They are viewed as the ´champions´ of gender equality regarding many aspects of life. [12] For example, regarding the labor market, 75% of Nordic women are employed. [13] This of course goes against traditional gender roles, and results in high independency. Additionally, more Nordic women than Nordic men complete tertiary education (see figure 5), in turn resulting in having a lot of resources. [14] Nordic women have a lot of opportunities, and all these things together could trigger intimate partner violence against women, according to this backlash effect.

Legal shortcomings

Every minute, 20 people are the victim of intimate partner violence in the United States [20]

70% of intimate partner violence worldwide goes unreported [21]

Reasons for non-reporting are fear for repercussions, access to services, little to no faith in the criminal justice system, or undermining the seriousness of their issue [19, 21]

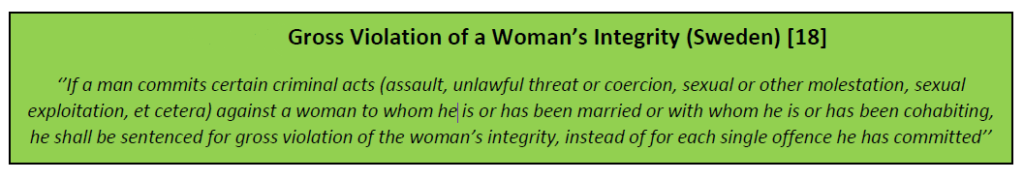

The last possible explanation that could be used for understanding the Nordic paradox takes on a legal perspective. Unfortunately, the criminal justice system often is ineffective when punishing those men who have been violent towards their partners. [15] Partly as a result, still not everyone reports intimate partner violence to the police. For example, in Norway, only one in four men and women report intimate partner violence, despite the fact that the police in Norway has tried to increase reporting of such offenses. [16] According to these women, non-reporting their experiences with intimate partner violence is a result of having little to no faith in the police, believing that the police wouldn’t be able to prevent violence from their partners in the future (i.e. to punish them properly). However, if women do in fact decide to report intimate partner violence, the criminal justice system still fails too often. Unfortunately, this is something that is common worldwide. [21] However, we do see that in Nordic countries, such as in Sweden, on average only 11% of alleged perpetrators are convicted of Gross Violation of a Woman’s Integrity (see figure 6) , whereas 56% of alleged perpetrators are not convicted at all. Overall, the criminal justice system in Sweden struggles heavily with handling intimate partner violence, according to research. Despite this strict law that was intended to improve the situation and that was implemented in 1998, there hasn’t been much change regarding this issue and there also hasn’t been done much to improve the law itself. However, what makes the situation of prosecuting the perpetrators even more difficult is not only the criminal justice system itself, but also the fact not many victims are willing to cooperate with the investigation of the police, making it difficult to press charges in the first place. [17]

Implications for the future

Even though there exist some explanations for the Nordic paradox, there hasn’t been enough research yet to make complete conclusions on what the exact mechanisms are behind the surprising positive relationship between gender equality and the prevalence of intimate partner violence in Nordic countries. However, what we do know is that Denmark, Finland and Sweden show high percentages of women experiencing intimate partner violence. Research on the effect of intimate partner violence has increased significantly over the past years, especially research on psychological violence. Overall, intimate partner violence can cause for several implications regarding many aspects of life, in particular when it comes to health, both physically and mentally.

Individual women’s’ health

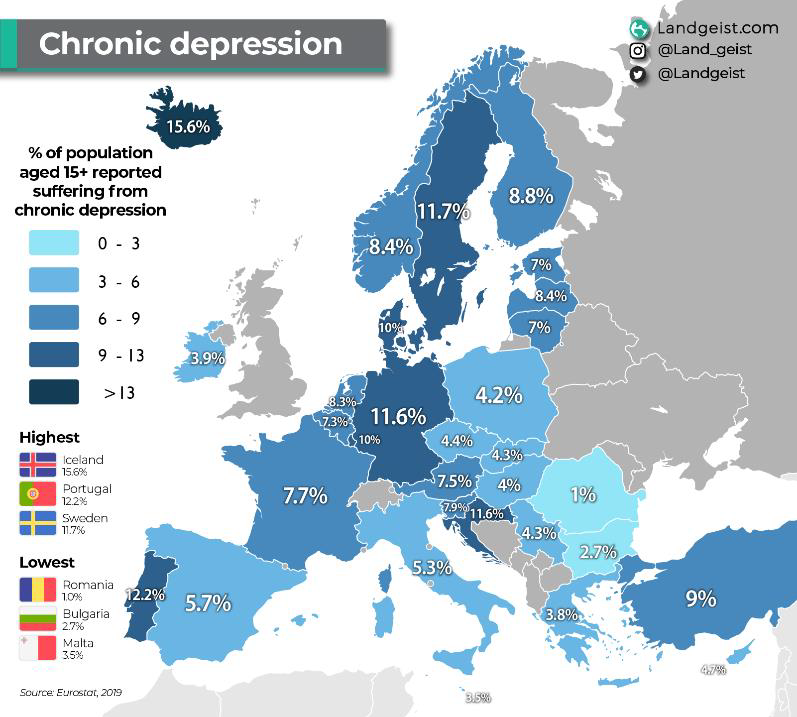

Studies in Europe have shown that women who experienced or are still experiencing intimate partner violence suffer more greatly from physical and mental symptoms compared to women without a history of intimate partner violence, and thus also have an increased risk of experiencing negative health outcomes. Women mostly reported to suffer from anxiety and sadness when being physically or sexually abused, whereas women who were being mentally abused more frequently reported being depressed. [19] In fact, looking at figure 7, you notice that Sweden and Iceland (another Nordic country) are in the top three countries regarding the percentage of the population aged 15+ who reported suffering from chronic depression, even though Sweden and Iceland are also currently in the top seven happiest countries in the world. [22]

The societal and economic impact

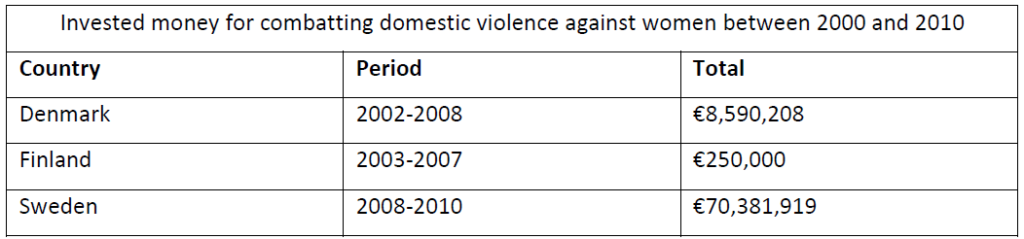

Intimate partner violence does not only have an impact on individual women’s physical and mental health, but also on society as a whole. Having high percentages of intimate partner violence is also associated with high economic costs: women suffering from domestic violence often are less productive during work and also often work fewer hours. These are effects on the short term. On the long term, the number of women participating in the labor market could decrease as a result of domestic violence, or they acquire less skills and education throughout their life. Additionally, as a result of high percentages of intimate partner violence in a country, more public resources are invested in health and judicial services (see figure 8). [23] Consequently, less money is invested in other public services that benefits other aspects of society. Another societal impact of domestic violence that is important to note is that there is not only a risk for partners or family of the domestic abusers, but also for the community as a whole. Not only law enforcement officers, but also bystanders could be injured. [24]

Recommendations

There is a problem, and there needs to be a solution. Many women in Nordic countries, in particular Denmark, Finland, and Sweden, are suffering: they are the subject of high levels of intimate partner violence. In a country where genders are viewed and measured as being equal, there needs to be an explanation and a solution to this ongoing issue of intimate partner violence, because it seems as if numbers won’t be dropping anytime soon despite numerous efforts and investments. As a result, women’s physical and mental health is worsened, economic costs are remaining high, there is less money for public investments, and society is not becoming a safer place. Therefore, there are a few recommendations for policymakers of the Nordic countries, in particular Denmark, Finland, and Sweden.

1 – Research. As already mentioned, there hasn’t been a clear nor comprehensive explanation yet to understand the Nordic Paradox. This is because of inefficient, insufficient, and inadequate research on the topic. Currently, researchers are separately trying to find the mechanisms behind the this paradox, whereas it would be beneficial to implement a research team investigating the issue. The main focus of research regarding this topic should be conducting qualitative interviews to see why women in Nordic countries experience such high levels of intimate partner violence and what the reasons are behind (non-)reporting such violence. If we can capture the exact mechanisms behind these high numbers of intimate partner violence in such gender-equal countries, and the reasons for reporting or non-reporting, we can more easily implement programs or other fitting solutions to solve the problem and improve the system.

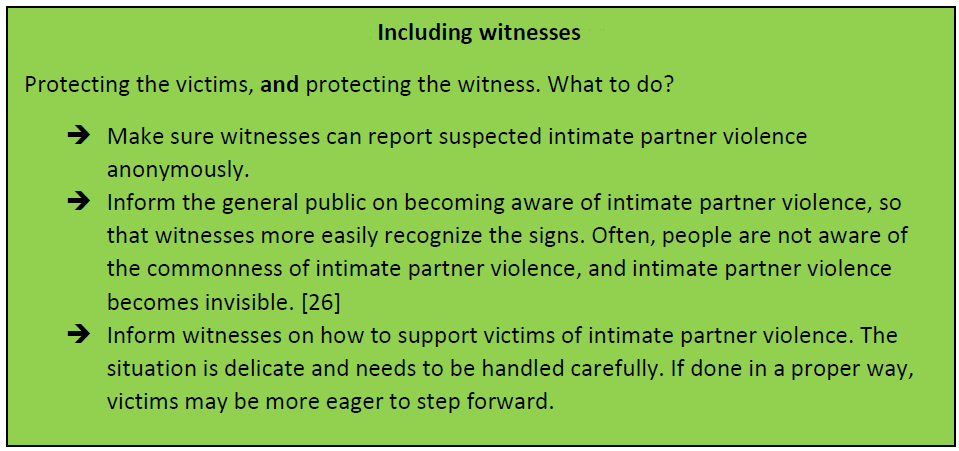

2 – Stimulating witnesses’ cooperation. Pressing charges against perpetrators becomes difficult if victims are not willing to cooperate, as already mentioned in the paragraph regarding the legal shortcomings. Research shows that victims often hesitate with pressing charges, as they for example have become normalized to the repeated violence. [19] Policies in Europe to tackle intimate partner violence have mainly focused on protecting the victim, whereas it would be beneficial to also turn to witnesses when trying to press charges. [25] In order for witnesses to be included in this process, there are a few options (figure 9). If more men are convicted, as a consequence there will not only be a decrease in intimate partner violence, but also more faith in the criminal justice system leading to less non-reporting and non-convictions.

3 – Educate and prevent. One option is to tackle an existing problem, another thing is to prevent it from happening in the first place. They often say that prevention is better than cure, and preventing intimate partner violence can be done in multiple ways, which is essential when trying to combat the issue. One important way to prevent is to educate. If you educate children at a young age on how to have safe and healthy relationships, the risk of domestic violence decreases, as research points out. [27] Therefore, implementing programs in which these things are taught in schools could be beneficial when trying to tackle the problem of domestic violence.

Referenties

- Victorian Government. (n.d.). Gender equality: what is it and why do we need it? Retrieved from https://www.vic.gov.au/gender-equality-what-it-and-why-do-we-need-it

- Save The Children. (n.d.). Gender Discrimination: Inequality Starts in Childhood. Retrieved from https://www.savethechildren.org/us/charity-stories/how-gender-discrimination-impacts-boys-and-girls#:~:text=Gender%20inequality%20is%20discrimination%20on,violated%20by%20gender%2Dbased%20discrimination.

- EIGE. (2022). Gender Equality Index 2022. Retrieved from https://eige.europa.eu/gender-equality-index/2022/country

- Global Development Commons. (2009). Promoting gender equality to prevent violence against women. Retrieved https://gdc.unicef.org/resource/promoting-gender-equality-prevent-violence-against-women

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Fast Facts. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/fastfact.html#:~:text=Intimate%20partner%20violence%20(IPV)%20is,former%20spouses%20and%20dating%20partners.

- Dolan and Zimmerman. (n.d.). Domestic Violence Statistics: A Comprehensive Investigation. Retrieved from https://www.dolanzimmerman.com/domestic-violence-statistics/

- De Laat, L., & Hampel, J. (March 16th, 2023). The Nordic Paradox: Violence Against Women in “Gender-Equal” Societies. Retrieved from https://www.theperspective.se/2022/04/26/article/the-nordic-paradox-violence-against-women-in-gender-equal-societies/#:~:text=Similarly%2C%20the%20occurrence%20of%20psychological,than%20elsewhere%20in%20the%20EU.&text=The%20positive%20relationship%20between%20violence,called%20the%20%E2%80%9CNordic%20Paradox%E2%80%9D.

- Leahy, E. (June 7th, 2016). “Nordic paradox”: highest rate of intimate partner violence against women despite gender equality. Retrieved from https://www.elsevier.com/connect/nordic-paradox-highest-rate-of-intimate-partner-violence-against-women-despite-gender-equality

- Permanyer, I., & Gomez-Casillas, A. (2020). Is the ‘Nordic Paradox’ an illusion? Measuring intimate partner violence against women in Europe. International Journal of Public Health, 65, 1169-1179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-020-01457-5

- Wiechmann, M. (2022). Gender-based Violence and the Nordic Paradox: When things are not what they seem – A short critical reflection. Journal of Comparative Social Work, 2, 79-89. https://doi.org/10.31265/jcsw.v17.i2.572

- Wemrell, M. (2023). Stories of Backlash in Interviews With Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in Sweden. Violence Against Women, 29(2), 154-184. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778012221088312

- OECD. (2018). Is the Last Mile the Longest? Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/els/emp/last-mile-longest-gender-nordic-countries-brief.pdf

- Nordic Co-operation. (March 7th, 2023). Labour market. Retrieved from https://www.norden.org/en/statistics/labour-market

- Nordic Co-operation. (March 6th, 2023. Education. Retrieved from https://www.norden.org/en/statistics/education

- Felson, R. B. (2008). The legal consequences of intimate partner violence for men and women. Children and Youth Services Review, 30, 639-646. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.01.005

- Grovdal, Y. (2019). «Not worth telling the police”. Intimate partner violence that has not been reported. Retrieved from https://www.nkvts.no/english/report/not-worth-talking-to-police-about-violence-in-close-relationships-that-are-not-reported-to-the-police/

- Strand, S. J. M., Selenius, H., Petersson, J., & Storey, J. E. (2021). Repeated and Systematic Intimate Partner Violence in Rural Areas in Sweden. International Criminology, 1, 220-233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43576-021-00026-x

- UN Women. (2023). Act on Violence against Women (Government Bill 1997/9855). Retrieved from https://evaw-global-database.unwomen.org/fr/countries/europe/sweden/1998/act-on-violence-against-women–government-bill-1997-98-55#:~:text=%E2%80%9CGross%20violation%20of%20a%20woman’s,shall%20be%20sentenced%20for%20gross

- del Rio, I. D., & del Valle, E. S. G. (2017). The Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence on Health: A Further Disaggregation of Psychological Violence—Evidence From Spain. Violence Against Women, 23(14), 1771-1789. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801216671220

- National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. (n.d.). National Statistics. Retrieved from https://ncadv.org/STATISTICS#:~:text=NATIONAL%20STATISTICS&text=On%20average%2C%20nearly%2020%20people,10%20million%20women%20and%20men.

- Gurm, B., & Marchbank, J. (n.d.). Chapter 8: Why Survivors Don’t Report. Retrieved from https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/nevr/chapter/why-do-survivors-not-report-to-police/

- World Population Review. (2023). Happiest Countries in the World 2023. Retrieved from https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/happiest-countries-in-the-world

- Ouedraogo, R., & Stenzel, D. (November 24th, 2021). How Domestic Violence is a Threat to Economic Development. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2021/11/24/how-domestic-violence-is-a-threat-to-economic-development

- Illinois Coalition. (2023). Societal Impacts of Domestic Violence. Retrieved from https://www.ilcadv.org/societal-impacts-of-domestic-violence/

- Hofman, J. (2020). What factors encourage witnesses of intimate partner violence to help? Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/randeurope/research/projects/witness-reporting-intimate-partner-violence.html

- Wemrell, M., Stjernlöf, S., Lila, M., Gracia, E., & Ivert, A. K. (2012). The Nordic Paradox. Professionals’ Discussions about Gender Equality and Intimate Partner Violence against Women in Sweden. Women & Criminal Justice, 32. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974454.2021.1905588

- Christiansen, S. (September 17th, 2020). How to Identify and Prevent Intimate Partner Violence. Retrieved from https://www.verywellhealth.com/intimate-partner-violence-prevention-4429117#:~:text=Prevention%2C%20education%20and%20screening%20programs,of%20IPV%20and%20their%20children.