In recent years, there has been a growing concern for the emergence of a gender pension gap (EIGE, 2022a). This gap signals an increase in inequalities in economic resources in old age and is associated with rising poverty rates among older women especially. In theory, pension systems play a role in correcting for these resource inequalities through various redistributive mechanisms (Ebbinghaus, 2021). One particular intervention is the introduction of care credits, which seek to compensate for the interrupted career patterns of parents. Such credits have been introduced in a number of countries, including Sweden (Frericks et al., 2008; Fultz, 2011; Jankowski, 2011). However, pension systems across the EU have also come under pressure and have undergone a series of reforms. This raises the question whether care credit systems are able to narrow the gender pension gap, especially within the context of structural pension reforms which have particular gendered effects.

The objective of this research note is to assess the gendered effects of pension reforms, and the role that the care credits in the Swedish pension system play in reducing these. In order to do so, the Swedish system will be compared with the Dutch pension system where care credits have not be introduced. Reform trajectories in both countries have caused a convergence of pension systems, which allows a comparison in terms of the performance of both systems in preventing old age poverty. Although it is not possible to establish causal links between the care credit system and gendered poverty outcomes, the comparison of both systems provides insight into specific pension design features and real-life outcomes for women. The question guiding this analysis is as follows:

How have pension reforms in Sweden and the Netherlands impacted gendered patterns of old-age poverty and (how) does the Swedish care credit system contribute to mitigating these effects?

To answer this question, a brief introduction is first provided regarding the gender pension gap. Secondly, the basic structure of the Swedish and Dutch pension systems will be sketched to provide a point of departure for the subsequent comparison. General reforms in both countries from the 1970s onwards are subsequently discussed with particular focus on their gendered impact. Third, the analysis zooms in on the effects of pension system reform on the gender pension gap by focussing on outcomes in old age since 2005. Finally, the results of the analysis will be discussed and contextualised.

The Gender Pension Gap and the gendered impacts of Pension System Reforms in the 1970s and 1990s

The Gender Pension Gap is broadly defined as the percentage by which women’s average pension is lower than men’s in a given country (EIGE, 2015, p. 47). This gap is considerable in size in most European countries, and researchers have pointed to an EU-wide tendency of this gap to increase in recent years (OECD, 2019). Although the gender pension gap can be attributed to multiple causes, a general consensus exists that it emerges out of structural gender differences in the labour market and the link between these and welfare and pension systems (Frericks et al., 2008, 2009; Samen Lodovici et al., 2016). The accumulation of gendered disadvantages over the individual’s life course however can be mitigated to an extent by the (re)distributive effects of pension systems (Ebbinghaus, 2021; Hammerschmid & Rowold, 2019).

In recent decades however, population ageing and the 2008 economic crisis in particular have challenged the (financial) sustainability of existing pension schemes. Consequently, pension systems have been adapted and restructured through a succession of measures (Palier, 2012; Samen Lodovici et al., 2016). Despite their initial differences, structural reforms of pensions systems in the Netherlands and Sweden have evolved along a somewhat common trend causing a convergence of both systems (Anderson, 2004). In Sweden, a more general welfare restructuring process took place in the 1970s which also impacted the pension system. More significant however has been the 1992/1994 reform of the pension system itself (Palmer, 2002; Sørensen et al., 2016). In The Netherlands, pension system reform has been a much more gradual process of incremental change, as is illustrated for instance by the gradual decoupling of the basic pension (AOW) and wages in the 80s and 90s through de-indexation (Bezemer, 2022; Delsen, 2007). Rather than to discuss each reform measure in detail, however, the following section will focus on general reform patterns and compare the resulting pension system characteristics.

Common Reform Trajectories: The Shift to a Multi-pillar Pension System

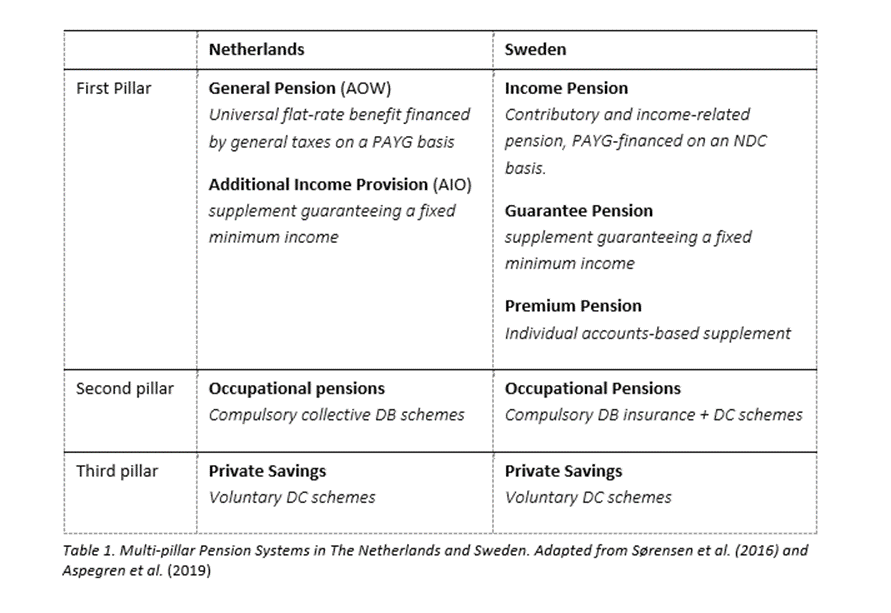

In many EU countries, scholars have observed a shift to multi-pillar pension systems (Samen Lodovici et al., 2016). In the Netherlands and Sweden too, first-pillar public pensions have been diminished in favour of employment-related occupational pensions and private funded pension schemes (Frericks et al., 2006). In the Netherlands, the first pillar consists of a minimum basic pension (AOW) which is provided by the state and benefits are not means-tested (Bovenberg & Meijdam, 2001). An additional income provision is furthermore available for individuals who do not receive a full old-age pension, for instance because they have spent part of their employment career abroad and therefore qualify for partial AOW entitlements only.

With the 1992/1994 reform, Sweden has switched from a basic-plus-earnings-related to a primarily earnings-related system (Ebbinghaus, 2021). Today, the first pillar consists of a notional defined contribution (NDC) Income Pension, which aims to compensate the replacement rate for workers below a defined ceiling (Palme, 2003; Sørensen et al., 2016). A further social assistance benefit (the Guarantee Pension) serves to fill the gap between the contribution-based Income Pension and a defined minimum income (Palmer, 2002). Of particular importance here is the supplementary Premium Pension in Sweden, which is a DC scheme based on individual accounts (Sørensen et al., 2016). Within this component, 2.5 percent of the individual’s annual salary is paid into a fund which goes towards their pension (Swedish Pensions Agency, 2022). It is in this part of the pension system where care credits are introduced.

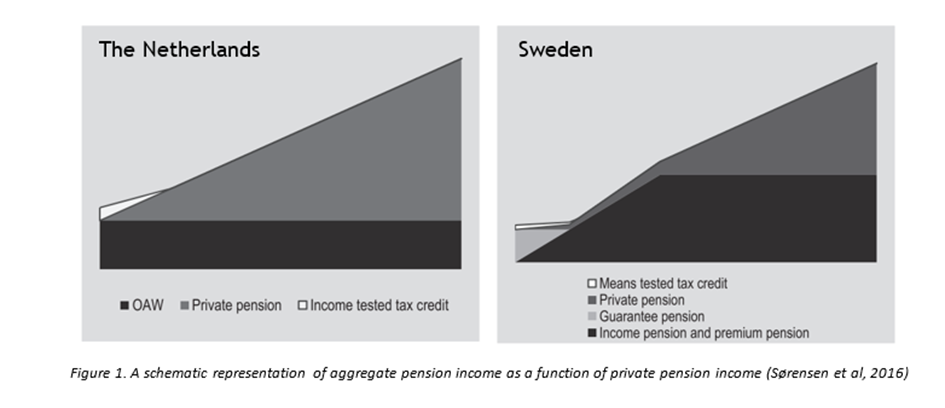

In the second pillar, both countries have quasi-mandatory occupational pensions which are defined through collective agreements (DB in the Netherlands and DB + DC in Sweden) (Palmer, 2002; Sørensen et al., 2016). Contrary to the Dutch system, the Swedish system has a replacement rate objective also in the second pillar. Consequently, “second pillar benefits are more important for workers with earnings above the income threshold of the first pillar” (Sørensen et al., 2016, p. 60). This means that private benefits play a large role especially for high-income pensioners (see figure 1). By contrast, the third pillar is relatively small in the Dutch pension system. Additionally, low income is also compensated by tax credits in both systems (the zero pillar) (Sørensen et al., 2016).

The gradual shift towards multi-pillar systems which combine PAYG and fully funded methods are thought to have a particular effect on the gender pension gap. In the context of gendered effects of pension reforms, three of these trends are particularly relevant to discuss.

Increasing emphasis on contribution

Pensions systems in Sweden and the Netherlands increasingly subject pension entitlements to the logic of accumulating contributions. The Bismarckian social insurance logic of the multi-pillar architecture strongly influences the reproduction of social inequalities that exists in the labour market in old age (Clasen & van Oorschot, 2002). Occupational and private pension schemes provide retirees with an income that allows them to maintain their previous living standard through horizontal redistribution. The increasing importance of these schemes disproportionately penalises women because fewer women tend to have supplementary pensions and if they do, the accrued amounts are often lower (Anderson & Meyer, 2006; Frericks & Maier, 2007). Additionally, pension norms for calculating occupational pensions are linked to a defined amount of contributing years. For instance, the criterion for receiving a ‘full pension’ in the Netherlands is set at 40 years. These norms are based on calculations which are meant to be gender neutral. However, women who are mothers often do not reach this norm and often have interrupted and part-time employment biographies (Frericks et al., 2006).

Individualisation of Pension Entitlements

In both countries, pension entitlements have also become more individualised over the past few decades (Frericks et al., 2006). This trend is most visible in Sweden, where individualized contribution accounts are incorporated not only in the state pension but also in individual retirement accounts (Frericks et al., 2008; Palier, 2012). In the Netherlands, on the contrary, the AOW is not entirely individualised as the level of pension benefit is affected by household composition (Anderson, 2004; Frericks et al., 2006). Still, some components of individualisation can be noted which have mixed effects on the pension entitlements of Dutch women. For instance before 1985 the AOW was couple-based, but it then changed to a mostly individual right so that women are entitled to a public pension independent of their partner (Anderson, 2012; Frericks et al., 2006). Importantly, however, partner allowances and survivors pensions are also phased out based on the (dubious) assumption that all women (or partners) will be employed and will no longer require additional supplements (Frericks et al., 2006).

Retrenchment and Minimum Income Protection

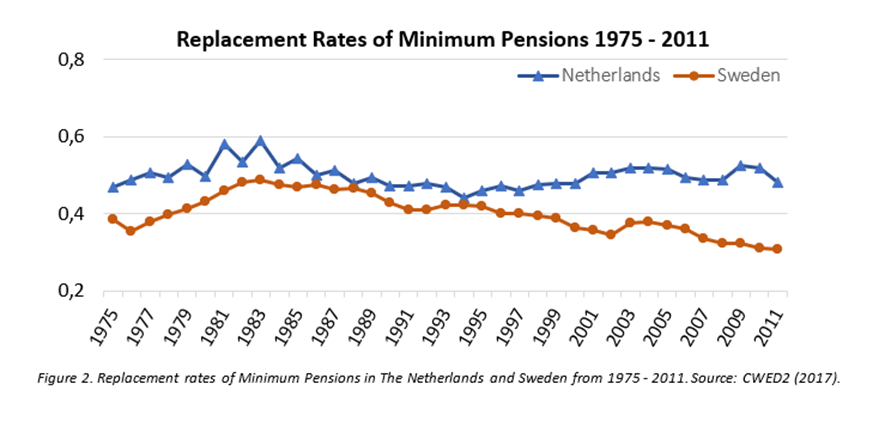

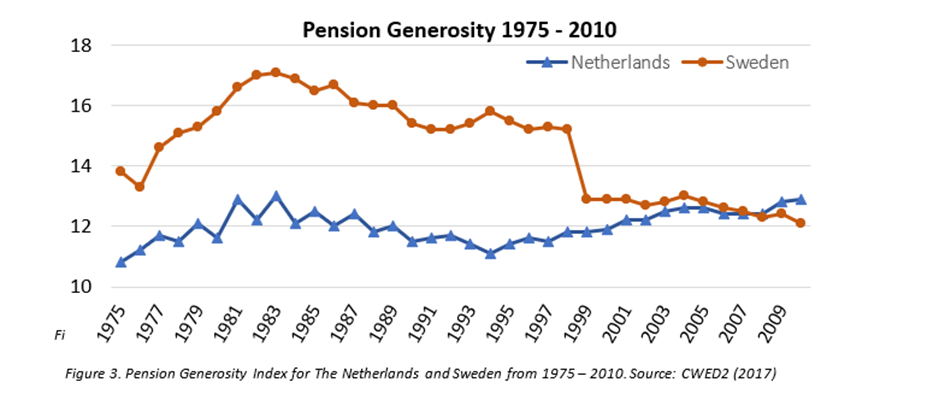

Finally, the shift to multi-pillar pensions systems in Sweden and the Netherlands has also affected the generosity of public pensions. Generally speaking, public pensions have a more vertical redistributive function in that they provide a poverty-preventing standard of living (Anderson, 2004; Blomqvist & Palme, 2020; Ebbinghaus, 2021; Palme, 2003). Again, this is of particular importance for women, who rely on guaranteed income schemes as a safety net if they have an incomplete career or relatively low earnings (D’Addio, 2012; Zaidi, 2010). With the shift to multi-pillar systems however, public pensions are gradually retrenched in Sweden and to a lesser extent also in the Netherlands (Anderson, 2004, 2012; Frericks et al., 2006). This trend is visible when looking at the replacement rates of minimum pensions since the 1970s (see figure 1).

In the Netherlands the decline is not initially evident, however when contrasting the minimum pension replacement rate with the parallel growth in overall public pension generosity (see figure 2), it is clear that minimum income provision has lagged. Furthermore, because the public pension is indexed to contractual wages, compared to the standard of living its actual value has gradually declined over the years (Frericks & Maier, 2007). In both countries, further retrenchment of public pension benefits are also predicted for the years after 2011 and for the future (Fultz, 2011). This contributes to a growing gap between people with access to occupational and private schemes and those without such access (Bonoli, 2012), causing broader inequalities among pensioners in general, but also between men and women of pensionable age.

Care Credits in the Swedish Pension System

As a result of the aforementioned reforms, the Dutch and Swedish pension systems have become gradually more similar. The Swedish system however includes a specific mechanism aimed at altering the gendered pension outcomes for women: the Care Credit System (D’Addio, 2012; Hammerschmid & Rowold, 2019; Jankowski, 2011). The rationale behind this system is that individuals who spend periods of time out of the labour market caring for children or other relatives qualify for lower pensions (D’Addio, 2012). To counter this, pension entitlements are increased by crediting time spend out of the labour market to care for children as a type of employment (Fultz, 2011; Jankowski, 2011).

The precise implementation of care credit systems varies cross-nationally. Differences exist in terms of the number of eligible years, the calculation of credits, and who is eligible (Jankowski, 2011). Since the 1970s, the Swedish state provides pension credits to parents with children under the age of four through transfers from the state budget to the social security system (Jankowski, 2011; Steinhilber, 2004). Credits are given for one child at a time and the level of the benefit is calculated either in relation to one’s own earnings (80%) or in relation to average earnings for all covered persons (75%) depending on the most favourable calculation (Palmer, 2002). There are also some eligibility criteria, such as a minimum requirement of 5 years of employment previously with earnings above a defined threshold (Fultz, 2011; Jankowski, 2011). Importantly, the Swedish care credit system is not targeted at women specifically: Technically, either one of the parents is allowed to take childcare credits. However if no preference is expressed, the default recipient is the parent with the lowest income in the relevant year. This is most often women (Hammerschmid & Rowold, 2019).

The effectiveness of care credits as a way to diminish the gender pension gap is unclear. The limited amount of research that exists primarily points to the fact that specific conditions are highly influential in determining the effect of such systems. For instance, recent projections by the OECD (2021) suggest that the hypothetical effect on actual gross pensions is visible only for periods spend out of labour market longer than 5 years. Moreover, the success of care credit systems in preventing gendered old-age poverty patterns is also moderated by other pension system reforms which may have specific effects on women. To explore these effects, the following section turns to one particular outcome of pension systems: old-age poverty risks.

Pension outcomes in Sweden and the Netherlands since 2000

Analysing the impact of pension reform is highly complex because retirement incomes by definition are a product of past events such as the pensioner’s earning history as well as pension rules in place at the time entitlements were built up (D’Addio, 2012). Reform measures may also be introduced in phases, as is the case for instance in the Swedish transition to NDC scheme (Aspegren et al., 2019). However, the Swedish care credit system has been introduced as early as the 1970s which means that current pensioners have benefitted at least to an extent from this system. Thus, because (a) a sufficient amount of time has passed since the introduction of the Swedish care credit system and (b) reform trajectories in the Netherlands and Sweden have been reasonably similar and synchronous, it is possible to assess the differential impacts of both systems on the position of women in old-age.

To do so, this analysis zooms in on old-age poverty as an outcome of pension system design inequalities using the at-risk-of-poverty indicator for the population over 65. This indicator reflects the share of people aged 65+ with an equivalised disposable income (after social transfers) below the at-risk-of-poverty threshold. In this case, this threshold is set at 60% of the national median income. The most recent indicator is provided for both countries from 2005-2021 by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE, 2022b). The indicators provided are based on the EU-SILC survey, and gender-segregated data are available. Using poverty-risk indicators it is possible to asses two things. First, by looking at the overall poverty rate of the population over 65, the adequacy of the system in preventing old-age poverty can be assessed. Secondly, by looking at the differential in the at-risk-of-poverty rate between men and women (aged 65+) it is furthermore possible to assess how both pension systems contribute to gender inequalities among pensioners.

Old-Age Poverty

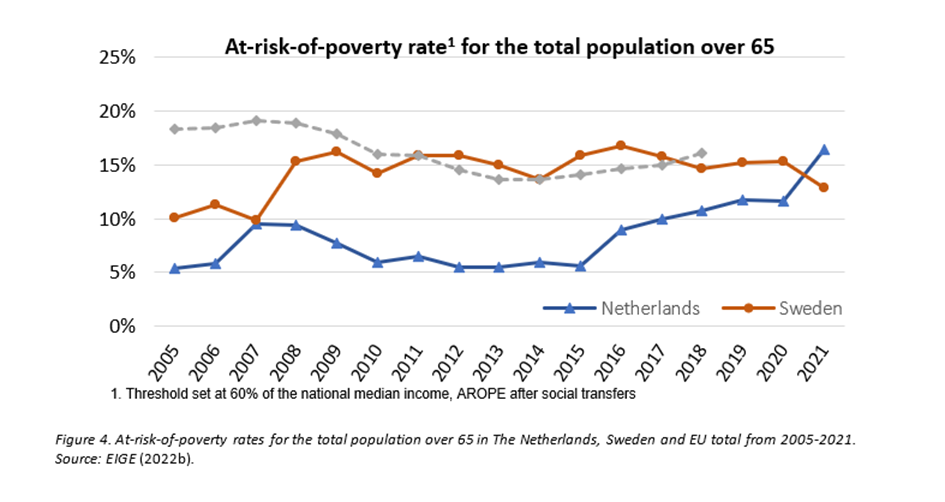

First of all, when looking at the at-risk-of-poverty rate for the total population over 65 it is evident that poverty rates have increased considerably in the Netherlands while they have remained more stable in Sweden (at least for post-crisis years, see figure 3). However, despite the relative stability, the poverty rate in Sweden has been somewhat higher than in the Netherlands until 2020. In the Netherlands, the old-age poverty rate has steadily increased since 2015 although it remains well below the total EU average.

Gender Inequality in Old-Age Poverty-Rates

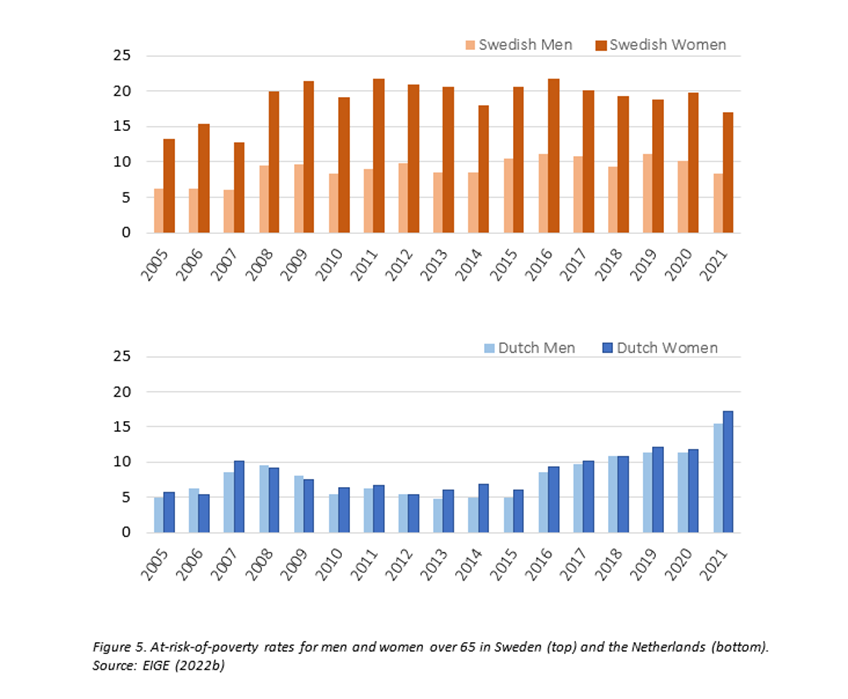

The differential in poverty rates between men and women over 65 shows a (surprisingly) similar picture (see figure 3). In the Netherlands, old-age poverty-rates increased for both men and women. Until 2020 however, old-age poverty rates in the Netherlands are at a much lower level than in Sweden, especially for women. In Sweden, old-age poverty-rates for women are significantly higher.

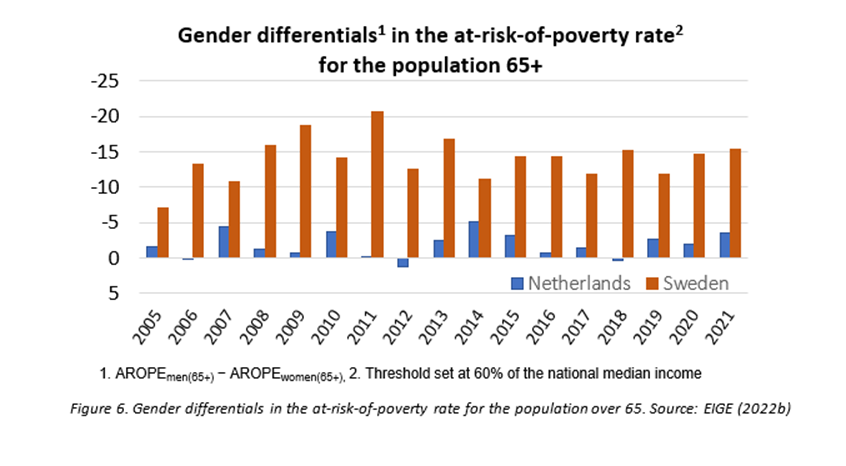

Zooming in on this gender differential, it is furthermore evident that gender differences in the Netherlands are not only lower but they are also much more stable over time, increasing only marginally over the whole time period (see figure 4). In 2012 and 2018, the at-risk-of-poverty-rate is even marginally higher for older men. In Sweden, by contrast, the gender differential in poverty rates fluctuates between -7.1 (2005) and -20.6 (2011). Overall, this gender gap has increased significantly (from -7.1 to -15.4).

Discussion and Conclusion

This analysis sought to assess the gendered impact of pension system reform in the Netherlands and Sweden and the mitigating effect of the Swedish care credit system by zooming in on old-age at-risk-of-poverty rates. Looking at the analysed trends, two relevant observations can be made. First, poverty rates in Sweden are significantly higher for women both compared to their male counterparts and to women in the Netherlands. However secondly, whereas both aggregate poverty rates and gender differentials have stabilised in recent years for Sweden (in fact showing slight improvements), Dutch old-age poverty-rates are increasing for both men and women since 2015.

On the one hand, these patterns relate to the ‘paradox of redistribution’, insofar as the system where the universal component of the pension system is more generous, the achieved redistribution is in fact higher (Gugushvili & Laenen, 2021). The Dutch system, where minimum pension replacement rates are higher and where the universal public pension is relatively generous, appears to be better able to avoid old-age poverty for both men and women. The generosity of first-pillar public pensions moreover also appears to be better able to restrain gender imbalance effects and to compensate for the relatively low level of second pillar benefits that are accrued across women’s employment biographies. This confirms earlier research, which has suggested that minimum income provision matters most for old-age poverty risks while the overall multi-pillar pension architecture impacts inequalities in old age (Ebbinghaus, 2021). Especially in Sweden, where contributivity is dominant both in first-pillar pensions and in second-pillar pensions, gender differentials in old-age poverty-rates are large and increasing.

What is perhaps more striking then is the lack of a reduction of gender differentials in old-age poverty risks in Sweden given the early introduction of the care credit system. There is no visible evidence of a positive effect of such credits on reducing gendered differentials in old age poverty especially in the context of other pension reforms with gendered impacts. By comparing the two countries, one might conclude that the gradual retrenchment of public pensions in Sweden strongly counters the positive effect that care credits potentially have on improving the economic security of women at old-age. Consequently, Swedish women are in fact at higher risk of poverty and this does not appear to be significantly improving.

Of course, this does not necessarily mean that care credits are on principle rejected. The apparent failure of the Swedish care credit system may be in part due to its technical specification. For instance, because the credits are (a) linked to contribution and (b) linked to income, their impact may be much bigger for higher income women (Jankowski, 2011). This gives rise to a Matthew Effect and effectively increases inequality between women causing higher poverty risks for low income women. To further asses the effectiveness of specific care credits systems, it may be relevant to compare countries where care credits have been introduced in order to determine under what provisions such systems are most effective in protecting women against old-age poverty.

Finally, several comments can be made with regards to the limitations of this analysis. First of all, the analysis largely disregards the extent of gender segregation in the Dutch and Swedish labour market. There is however evidence that suggests that there may be differences both in terms of female labour participation and gender-segregated work patterns (Mandel, 2009). In turn, these different patterns of inequality may result in differential access to especially occupational pension benefits.

Secondly, if the gender pension gap is more clearly related with labour market structures than with pension system design features (as the analysis suggests) this also implies that pension systems, however well-designed, will not be able to compensate on a large scale for inequalities between men and women or parents and the childless in the labour markets. Mitigating gendered old-age poverty patterns requires a more radical shift away from “male norms and female adjustments” (Frericks et al., 2008, p. 97). At best then, childcare credits are only one part of the equation when it comes to income redistribution and poverty among the elderly.

References

Anderson, K. M. (2004). Pension politics in three small states: Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands. Canadian Journal of Sociology, 29(2). https://doi.org/10.2307/3654697

Anderson, K. M. (2012). The Netherlands: Reconciling Labour Market Flexicurity with Security in Old Age. In K. Hinrichs & M. Jessoula (Eds.), Labour Market Flexibility and Pension Reforms: Work and Welfare in Europe (pp. 203–230). Palgrave Macmillan.

Anderson, K. M., & Meyer, T. (2006). New Social Risks and Pension Reform in Germany and Sweden: The Politics of Pension Rights for Childcare. In K. Armingeon & G. Bonoli (Eds.), The Politics of Post-Industrial Welfare States: Adapting Post-War Social Policies to New Social Risks (pp. 171–191). Routledge.

Aspegren, H., Durán, J., & Masselink, M. (2019). Pension Reform in Sweden: Sustainability and Adequacy of Public Pensions (No. 048; European Economy Economic Briefs).

Bezemer, D. J. (2022). Explaining the Growth of Funded Pensions: A Case Study of the Netherlands (No. 213; IMK Working Papers).

Blomqvist, P., & Palme, J. (2020). Universalism in Welfare Policy: The Swedish Case beyond 1990. 8(1), 114–123. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v8i1.2511

Bonoli, G. (2012). Active labour market policy and social investment: A changing relationship. In B. Palier, J. Palme, & N. Morel (Eds.), Towards a Social Investment Welfare State?: Ideas, Policies and Challenges (pp. 181–204). Policy Press.

Bovenberg, A. L., & Meijdam, L. (2001). The Dutch Pension System. In A. H. Börsch-Supan & M. Miegel (Eds.), Pension Reform in Six Countries (pp. 39–67). Springer.

Clasen, J., & van Oorschot, W. (2002). Changing Principles in European Social Security. European Journal of Social Security, 4, 89–115.

D’Addio, A. C. (2012). Pension entitlements of women with children: The role of credits within pension systems in OECD and EU countries. In Nonfinancial Defined Contribution Pension Schemes in a Changing Pension World (pp. 75–111). World Banks.

Delsen, L. W. M. (2007). De hervorming van de verzorgingsstaat in Nederland: 1982-2003. Belgisch Tijdschrift Voor Sociale Zekerheid, 4(48), 633–666.

Ebbinghaus, B. (2021). Inequalities and poverty risks in old age across Europe: The double-edged income effect of pension systems. Social Policy & Administration, 55(3), 440–455.

EIGE. (2015). Gender Gap in Pensions in the EU – Research note to the Latvian Presidency.

EIGE. (2022a). Policy cycle in poverty. European Institute for Gender Equality. https://eige.europa.eu/gender-mainstreaming/policy-areas/poverty/policy-cycle

EIGE. (2022b, December). Gender Statistics Database. European Institute for Gender Equality. https://eige.europa.eu/gender-statistics/dgs

Frericks, P., Knijn, T., & Maier, R. (2009). Pension Reforms, Working Patterns and Gender Pension Gaps in Europe. Gender, Work & Organization, 16(6), 710–730.

Frericks, P., & Maier, R. (2007). The Gender Pension Gap: Effects of Norms and Reform Policies. In M. Kohli & C. Arza (Eds.), The Political Economy of Pensions: Politics, Policy Models and Outcomes in Europe (pp. 175–195). Routledge.

Frericks, P., Maier, R., & de Graaf, W. (2006). Shifting the Pension Mix: Consequences for Dutch and Danish Women. Social Policy & Administration, 40(5), 475–492.

Frericks, P., Maier, R., & de Graaf, W. (2008). Male Norms and Female Adjustments: The Influence of Care Credits on Gender Pension Gaps in France and Germany. European Societies, 10(1), 97–119.

Fultz, E. (2011). Pension Crediting for Caregivers: Policies in Finland, France, Germany, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Japan. www.iwpr.org

Gugushvili, D., & Laenen, T. (2021). Two decades after Korpi and Palme’s “paradox of redistribution”: What have we learned so far and where do we take it from here? Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy, 37(2), 112–127. https://doi.org/10.1017/ICS.2020.24

Hammerschmid, A., & Rowold, C. (2019). Gender Pension Gaps in Europe are more explicitly associated with labor markets than with pensions systems. In DIW Weekly Report.

Jankowski, J. (2011). Caregiver Credits in France, Germany, and Sweden: Lessons for the United States. Social Security Bulletin, 71.

Mandel, H. (2009). Configurations of gender inequality: the consequences of ideology and public policy. The British Journal of Sociology, 60(4), 693–719.

OECD. (2019). Wide Gap in Pension Benefits between Men and Women. The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1455-6_CH18

OECD. (2021). Pensions at a Glance 2021: OECD and G20 Indicators (OECD Pensions at a Glance). OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/19991363

Palier, B. (2012). Turning Vice into Vice: How Bismarckian Welfare States Have Gone from Unsustainability to Dualization. In G. Bonoli & D. Natali (Eds.), The Politics of the New Welfare State (pp. 233–253). Oxford University Press.

Palme, J. (2003). Pension Reform in Sweden and the Changing Boundaries between Public and Private. In G. L. Clark & N. Whiteside (Eds.), Pension Security in the 21st Century: Redrawing the Public-Private Debate (pp. 144–167). Oxford University Press.

Palmer, E. (2002). Swedish Pension Reform: How Did It Evolve, and What Does It Mean for the Future? In M. Feldstein & H. Siebert (Eds.), Social Security Pension Reform in Europe (pp. 171–210). University of Chicago Press.

Samen Lodovici, M., Drufuca, S., Patrizio, M., & Pesce, F. (2016). The Gender Pension Gap: Differences between Mothers and Women Without Children.

Sørensen, O. B., Billig, A., Lever, M., Menard, J. C., & Settergren, O. (2016). The interaction of pillars in multi-pillar pension systems: A comparison of Canada, Denmark, Netherlands and Sweden. International Social Security Review, 69(2), 53–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/ISSR.12101

Steinhilber, S. (2004). The Gender Implications of Pension Reforms. General Remarks and Evidence from Selected Countries 1. In UNRISD report: Gender Equality: Striving for Justice in an Unequal World (Gender Equality: Striving for Justice in an Unequal World).

Swedish Pensions Agency. (2022). The Swedish pension system. Pensionsmyndigheten. https://www.pensionsmyndigheten.se/other-languages/english-engelska/english-engelska/pension-system-in-sweden

Zaidi, A. (2010). Poverty Risks for Older People in EU Countries – An Update. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/11867529.pdf