From magnizdat to feminist-punk

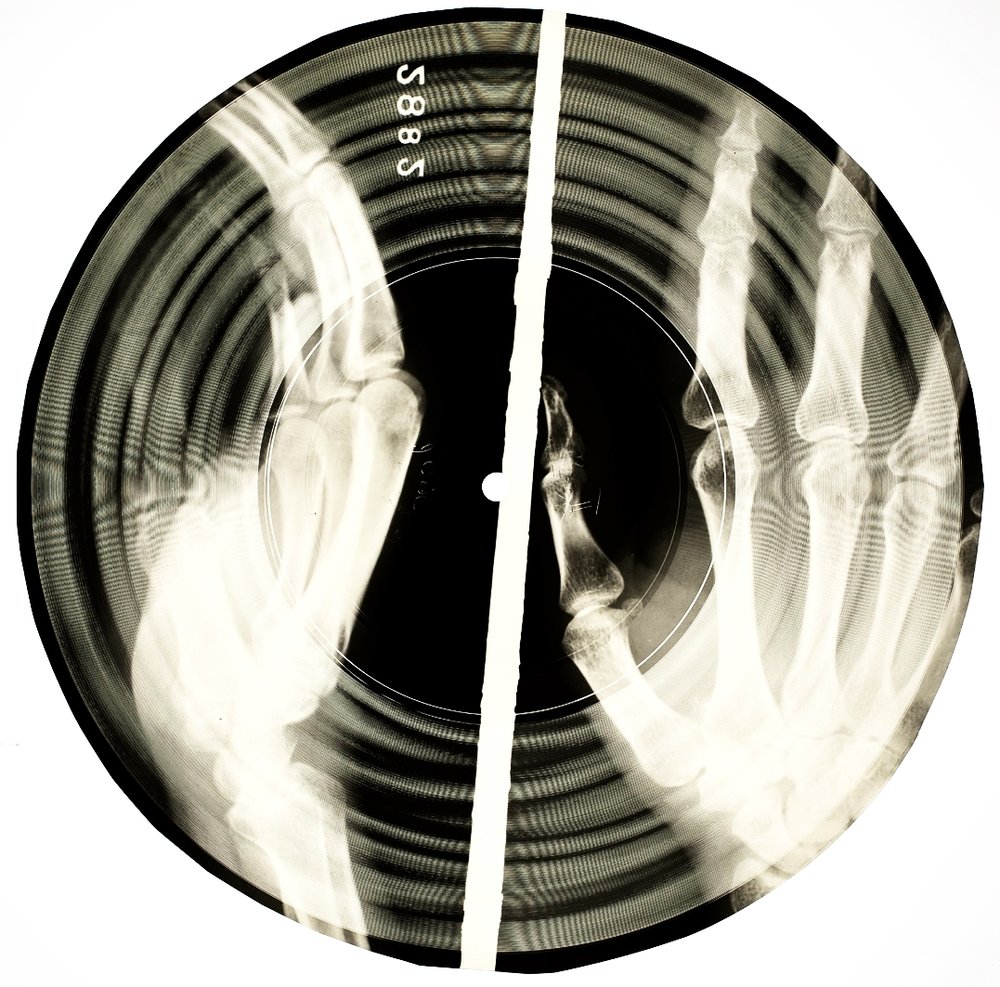

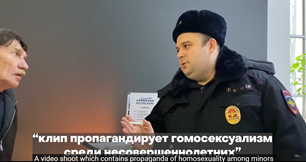

Take a look at the picture to the left. You might find it beautiful aesthetically, if you like bones. But this record was not made like this for its macabre appearance, but out of necessity. It’s a ‘bone’ record made of x-ray, created as a protest record in the USSR [1]. Nowadays, Russia is a conservative, patriotic and orthodox-Christian country, which claims to be democratic [2]. Their patriotism can be heard through songs like Вперед, Россия! (Forward, Russia!). Addressing progressive values such as the acceptance of LGHTBQ+ or feminist issues in an authoritarian country such as Russia is a dangerous act and there’s lots of opposition to it and thus, if one values human rights, this struggle is still very relevant [3]. Seemingly, cultural methods are still used in Russia to protest, as can be seen in the actions of Pussy Riot, a feminist, anti-authoritarian social movement and punk band. However, one could wonder what the function of music could be for social movements and if it’s enough to change the world. I shall try to compactly address this question and use Pussy Riot as the main example in this blog.

Music as a tool for change

Cultural methods are a way for movements to politically express themselves, change public opinions and put pressure on authorities [4]. Also, music has helped movements in articulating grievances and building solidarity amongst their target group [5]. Furthermore, the construction of a frame and a collective identity can lead to higher commitment and mobilization of supporters, but may be counterproductive in influencing policy makers [6][7][8]. Pussy riot has performed multiple actions to diffuse their ideas and mobilize people: a music-protest in a metro, calling out for a national uprising against Russia’s authorities in the Red Square [9] and they’ve entered Moscow’s main orthodox cathedral to pray that the Virgin Mary would become a feminist and chase Putin away [10]. However, this led to two years of imprisonment due to hooliganism motivated by religious hatred [11]. And even though a poll showed 6% of the Russians were sympathetic towards Pussy Riot, 44% didn’t think a prison sentence was appropriate [12][13] and thus their trial led to worldwide debates about the movement’s goals. So, this radical form of cultural action helped the movement to spread their message and helped to increase mobilization, as can be seen in their newer videoclips. But also, their conviction attributed to the debate around the issue of criminalization of social movements [14].

Going beyond borders

In trying to change patterns of cultural authority, a debate is not enough, and a movement could look beyond its borders to change the world. Movements can also mobilize other organizations, which could offer them new resources or better preparations for protest [15]. This could be done in person or online. The internet created a way for movements to easily gain a trans-national character and for rapid diffusion of ideas. In the case of Pussy Riot, this is done via YouTube [16]. The interaction between Pussy Riot and the state added to the process of the groups’ dynamics and thus changed what is called the configuration of actors: their views on human rights violations changed and the struggle of Russian prisoners became part of their cause. Due to these changes, different members left the group and two members eventually started a human rights organization called Law Zone [17][18]. Social movements becoming organizations is not entirely new, it’s often needed to survive [19]. Law Zone launched a broader campaign encompassing all their values and beliefs and called upon the UN to pressurize Russia [20]. Additionally, they’ve spoken in different settings, such as universities and music festivals, and reached many people via Twitter. Nowadays, they use their organizational infrastructure to work together with different organizations worldwide to deliver their messages about human rights, but they were stamped by Putin as ‘foreign agents’ and thus organized campaigns in which 222 other organizations joined, to defend independent media organizations [21]. Where this will lead remains to be seen.

Has the world changed?

Even though it’s incredibly hard to assess whether music as a form of action is enough to change the world, polls are a way to see if opinions have changed concerning the tolerance of homosexuals in Russia has increased [22]. However, it’s hard to assess whether part of this change in beliefs is due to Pussy Riots actions, so music may not directly change the world. But, music did pave the way for the movement to gain attention, make their message heard internationally, gain international support and even gave them the organizational tools to create an organization which is capable of mobilizing people, groups and form a more hardened oppositional front to Putin’s Russia. And a strong cultural opponent, just like Magnizdat in the USSR, is a force to be reckoned with for Russian hegemony.

Referenties

[1] Brown, A. (2010). De Opkomst En Ondergang Van Het Communisme (2de ed.). Spectrum.

[2] Petro, N. N. (2018). How The West Lost Russia: Explaining the Conservative Turn in Russian Foreign Policy. Russian Politics. 3(3), 305-332. https://doi.org/10.1163/2451-8921-00303001

[3] Yates, R. (2015). Extreme Russia. – 2. Gay under attack [Documentary]. BBC

[4] Taylor, V. and Van Dyke, N. (2004). ‘Get up, stand up’: Tactical repertoires of social movements. In D.A. Snow, S.A. Soule, and H. Kriesi (Eds), The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, Oxford, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, pp. 262-293

[5] Soule, and H. Kriesi (Eds), The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, Oxford, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, pp. 262-293

[6] Hunst, S.A. and Benford, R.D. (2004) Collective Identity, Solidarity, And Commitment. In D.A. Snow, S.A. Soule, and H. Kriesi (Eds), The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, Oxford, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, pp. 433-458

[7] Taylor, V. and Van Dyke, N. (2004). ‘Get up, stand up’: Tactical repertoires of social movements. In D.A. Snow, S.A. Soule, and H. Kriesi (Eds), The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, Oxford, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, pp. 262-293

[8] Amenta, E., Caren, N., Chiarello, E and Yang, S. (2010) The Political Consequences of Social Movements. Annual Review Sociology, 36, 287-307

[9] Zabyelina, Y. and Ivashkiv, R. (2017). Pussy Riot and the Politics of Resistance in Contemporary Russia. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice. Published. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.208

[10] Yusupova, M. (2014). Pussy Riot: a feminist band lost in history and translation. Nationalities Papers, 42(4), 604-610.https://www.academia.edu/7820078/Pussy_Riot_a_feminist_band_lost_in_history_and_translation

[11] Yusupova, M. (2014). Pussy Riot: a feminist band lost in history and translation. Nationalities Papers, 42(4), 604-610.https://www.academia.edu/7820078/Pussy_Riot_a_feminist_band_lost_in_history_and_translation

[12] Zabyelina, Y. and Ivashkiv, R. (2017). Pussy Riot and the Politics of Resistance in Contemporary Russia. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice. Published. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.208

[13] Yusupova, M. (2014). Pussy Riot: a feminist band lost in history and translation. Nationalities Papers, 42(4), 604-610.https://www.academia.edu/7820078/Pussy_Riot_a_feminist_band_lost_in_history_and_translation

[14] Zabyelina, Y. and Ivashkiv, R. (2017). Pussy Riot and the Politics of Resistance in Contemporary Russia. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice. Published. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.208

[15] Gerhards, J. and Rucht, D. (1992). Mesomobilization: Organizing and Framing in Two Protest Campaigns in West Germany, American Journal of Sociology, 98(3), 555-596.

[16] Van Laer, J. and Van Aelst, P. (2010). Internet and Social Movement Action Repertoires, Information, Communication & Society, 13:8, 1146-1171, DOI: 10.1080/13691181003628307

[17] Kriesi, H. (2004) Political Context and Opportunity in D.A. Snow, S.A. Soule, and H. Kriesi (Eds), The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, Oxford, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, pp. 67-90

[18] Zabyelina, Y. and Ivashkiv, R. (2017). Pussy Riot and the Politics of Resistance in Contemporary Russia. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice. Published.

[19] McAdam, D., McCarthy., J.D. and Zald, M.N. (1996). Introduction: Opportunities, mobilizing structures, and framing processes – toward a synthetic, comparative perspective on social movements. In D. McAdam, J.D. McCarthy, and Zald, M.N. Comparative perspectives on social movements: Political opportunities, mobilizing structures, and cultural framings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (pp. 1-20)

[20] Zabyelina, Y. and Ivashkiv, R. (2017). Pussy Riot and the Politics of Resistance in Contemporary Russia. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice. Published.

[21] Litvinova, D. (2021, 29 September). Russia Labels Media Outlet, 2 Rights Groups “Foreign Agents”. Newsmax.

[22] The Moscow Times. (2021, 21 Oktober). Russian Support for LGBT Rights Hits 14-Year High, Poll Says. Russian Support for LGBT Rights Hits 14-Year High, Poll Says – The Moscow Times